In March 2021, amidst the lockdown banalities and uncertainties, The Guardian newspaper ran an article on how mirror-selfies were now being faked. It was part of the continuation of restricted conditions coming up against the unceasing urge to continue habits of self-documentation and promotion under a watching-to-be-watched brief of structured reality. The idea, said the article, was that there was no mirror, only a second camera(phone) taking a photograph of someone looking into their phone pretending to be facing a mirror.

The article continued with an ultra-condensed debate about aesthetics, artifice and authenticity – how these three A-words swirl around and react to provoke strange behaviours in the online social media world. The article does not show any faked mirror-selfies, only ‘actual’ ones, and it is hard to imagine how they can be constructed without having to dispense with exposing the mirror frame which delineates between the surfaces in front of and behind the camera-phone. Instead, it is all about the deportment of the body and facial artifice of staged absorption and partial obscuring.

Which brings me to one of my favourite artists, the Canadian photographer Jeff Wall. Picture for Women (1979) was one of two breakthrough works that Wall produced to set out his position of creating photographs that were restructured both as artworks and as drawing from artworks. However, we can momentarily step back from Wall’s default rebus mode and the consequential standard game of deciphering that the critics play, to appreciate the pure aesthetics of the work.

Wall, in the photograph, has a great post-punk new-wave look and he knows it. Perhaps this is the meaning of a picture for women… Wall celebrating his just-so style: “here I am”. He is seen side-on, emphasising his sleek figure, accentuated with a plain black tee tucked into a narrow black belt and trousers. A minimally designed watch has a black strap and a rectangular face that catches the glare of the flash. His hair is sculpted and slick, pushed back into a 50s style that meets the 80s mullet-to-be. The arrangement of ceiling lights and furniture are also very new-wave, resounding with that Sol LeWitt geometric certainty. And there’s the colour-not-colour of the whole pictorial ensemble, a muted technicolour of black and white – it’s hard to explain, but oozes post-punk knowingness and archness.

In the same year Wall also produced Double Portrait where he creates a bemused pairing of himself with himself in a sublimely nondescript front room….

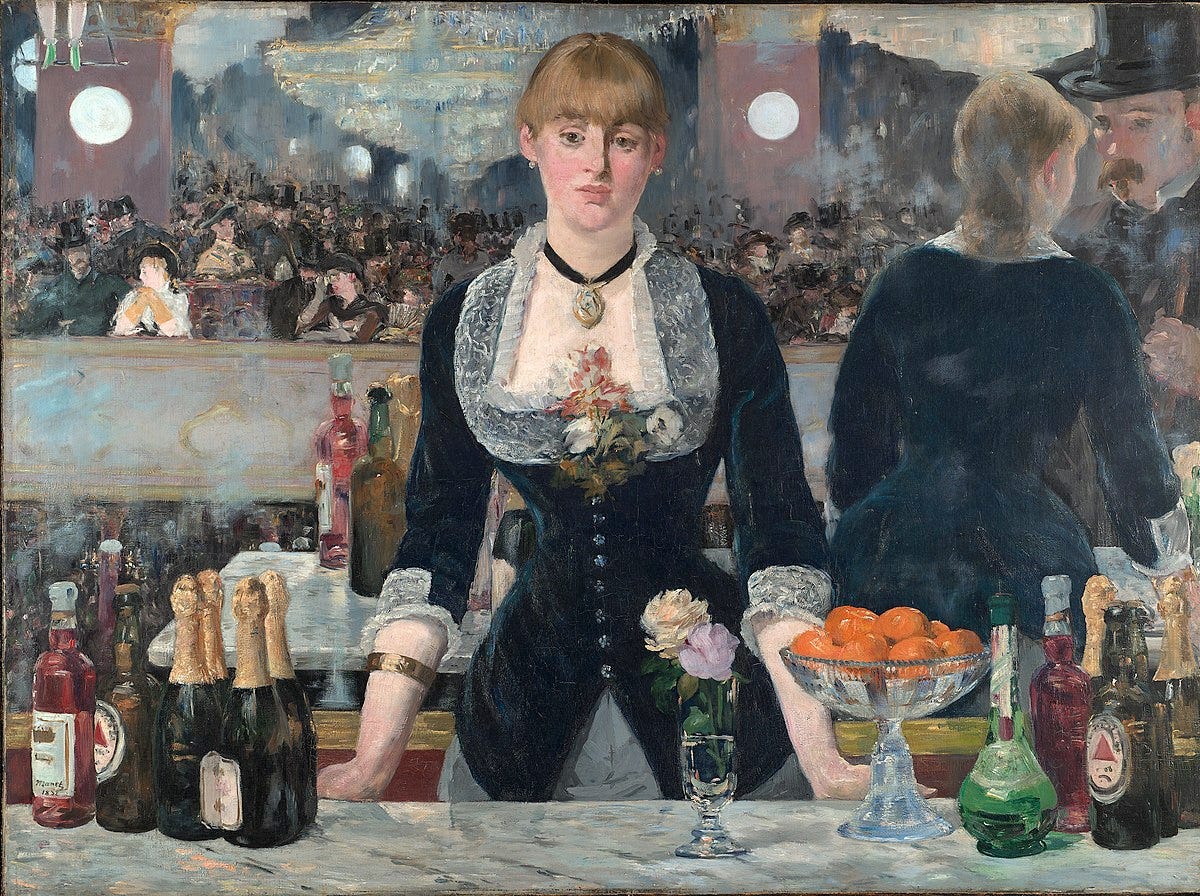

Let’s get back to the main game and share some of the agreed written theory on this photograph. Picture for Women draws from several sources, though (as with many of Wall’s works) these are open to investigation and interpretation. A popular suggestion for this work is the famous 1882 painting Un bar aux Folies Bergère by Édouard Manet, in which the artist takes liberties with how the view is depicted in terms of aspects in front of and behind the mirror. Though ostensibly a work about class and the painting of everyday people (as per the very meticulous arguments of TJ Clark), the enantiomorphic structure (objects both in front of and behind the mirror) does not cohere.

Wall takes this to be an important motif in his work. What we are given within the entirety of the photograph’s frame is also entirely drawn from a large mirror such as the wall-mounted structure in a gymnasium or dance studio. There appears to be no ‘not mirror’ captured by the camera – although (as I try to develop below) this is not quite the case, and needs further manipulation by the artist to achieve.

Critics tend to agree that the lines of sight and gazes are important, potentially making statements (or raising questions and/or uncertainties) about the male gaze and the querying as to the meaning of the title Picture for Women. It extends the visual culture terminology from what a picture or photograph is of and about, to who it is for.

The camera is positioned furthest back, on a tripod, and it faces directly into the mirror. Wall stands to the right, slightly forward of the camera, overtly pressing the shutter release with an extended wire and button – his view is directed at the woman’s mirror image, perhaps a point made about mediated desire. The woman is furthest forward, to the left of the arrangement, and she has a view slightly skewed into the lens of the camera in the mirror such that the resultant photograph has her as a possible subject, looking into the lens and so looking into the gaze of the viewer who patronises the resultant artwork.

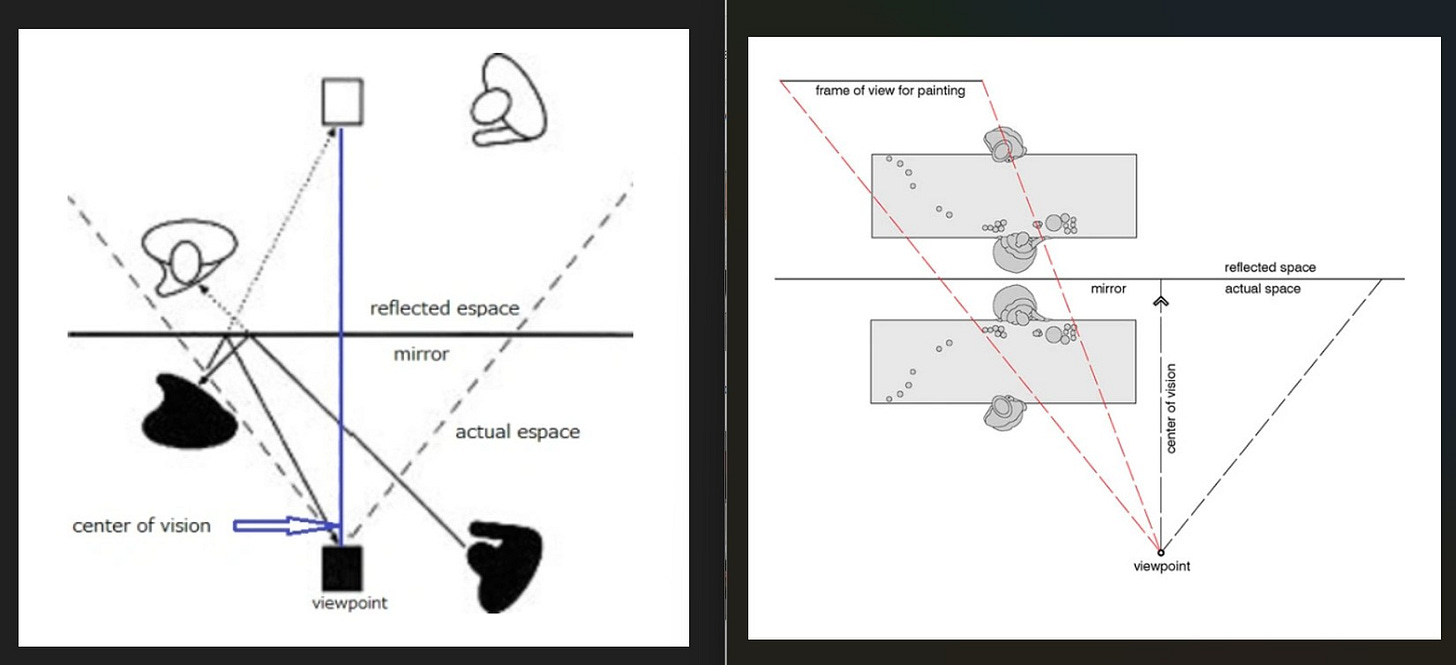

People have tried to schematicicise the arrangement, placing it alongside a similar schematic of Manet’s painting. It’s cracking stuff, and is worth spending a long moment to study and absorb. Art theorist Thierry de Duve in the Phaidon ‘Contemporary Artists’ series book on Wall calls on this (possible) bird’s-eye view of the ensemble, attempting to understand its spatial logic and concluding that this photograph renders the invisibility of the picture plane. In this regard, we might technically, albeit tentatively, also call this photograph Picture of a Man Looking at a Woman Watching a Camera Take a Photograph of Itself.

But if you step away from the puzzle of assigning stances and sight-lines it gets more complex – the Manet effect is introduced as Wall discreetly channels the illusionistic prowess of the artist. Two vertical steel poles approximately trisect the space of the image, demarcating three zones for the woman, the camera and Wall himself. In art-classical terms, a triptych. Optically, with a cursory glance, we might assign these as partition structures of the wall-mounted mirror, a Gestalt instinct, but they are actually standing on the floor – studio spotlights openly revealed by the cabling glimpsed on the left-hand structure and tripod foot glimpsed on the other. The glowing brightness of the woman suggests they are both trained on her region of the mirror.

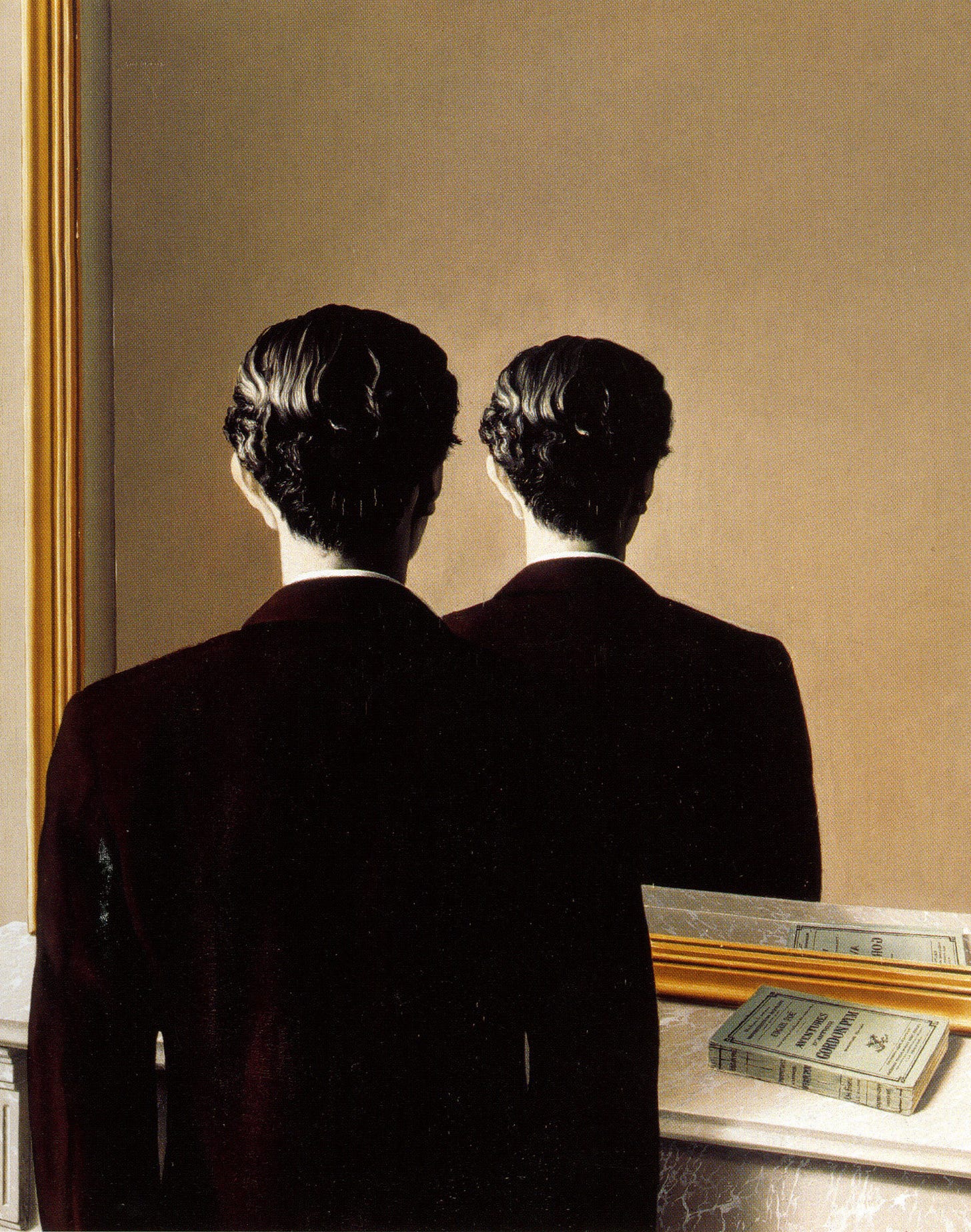

If you look again at the proposed schematic of Picture for Women you realise that a photograph showing the reflected space of a mirror must also show a triangular slice of the real space (or ‘actual space’ to use the terminology of the schematic) in front of the mirror. In a mirror-selfie, and in Wall’s photograph, this is a void, creating an optical illusion of a ‘pure’ reflected space that masquerades as a real space. However, the entirety of the reflected space must include the triangle of real space doubled-up and superimposed. If you imagine an object or third figure in the triangle of real space facing the mirror then it would appear twice in the final photograph – once from behind and a second time reflected from the front. This doubling allows the surrealist painter René Magritte to play with convention for his famous work La Reproduction Interdite (Not to Be Reproduced) from 1937.

In the Magritte work a French copy of the book The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (Les aventures d’Arthur Gordon Pym) by Edgar Allan Poe is visible on the mantelpiece on the lower right corner. Contrary to the man’s reflection, the reflection of the book in the mirror is correct.

The aspect of Picture for Women that troubles me is the wooden beam or shelf that the woman rests her hands on. She mimics the bored nonchalance of Manet’s figure and the aesthetic synergy between the two images is emphasised by Wall introducing the wooden beam to stand in for the marble-top bar of the painting. Both add to the illusionistic effect in a paired manner.

You feel that Wall’s wooden beam or shelf is tight up against the mirror, a kind of shelf for peripheral items, but this cannot be. If the woman were pressed up close to the mirror by resting against a shelf fixed to the mirror-wall, then the camera would also capture her back in the ‘real space’. She would be represented in the picture twice. This means that the beam/shelf is standing free from the mirror-wall, which would mean it would reside in the triangle of real space within the total extent of the resultant photograph. But the beam/shelf, like the woman, is only there once.

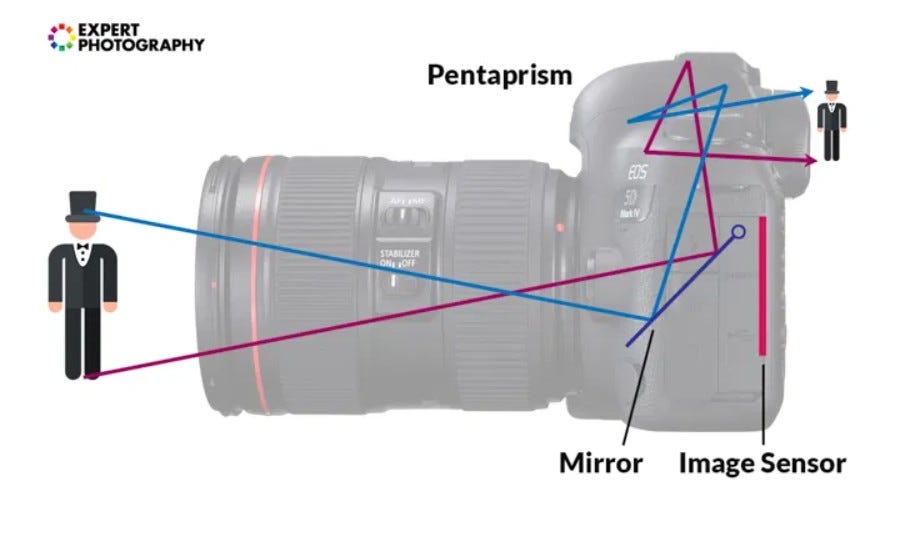

There is (I think) one possible explanation to this. The schematic is what it says – a flattened representation of position and sight-lines of both devices and glances. However, the camera lens extends as a 3-dimensional seeker of subjects and scope (technically, it is a funnel that captures the visible extent). And so, the real space is not a triangle but (on the basis of a circular aperture) a truncated cone that is flattened onto the rectangular ‘picture plane’ of the camera’s image sensor.

This is not the best image, as it is also ‘flattened’, but in the vertical plane. What would be best would be something resembling an Anthony McCall cone of light diagram.

Thus, Wall could create the resultant photograph by cropping the necessarily incorporated bottom section of the photograph which would include the beam/shelf in the real space and also the lower peripherals which presumably were captured in the original reflected space (Wall’s and the model’s legs, the lowest part of the camera tripod and feet of the light poles, more of the floor, etc). If I had time, and someone with me, I might have experimented in our big horizontal bathroom mirror. Maybe later.

But there’s more. Photographic theorist and Wall-fan David Campany, in an obsessive and frustrated monographic work on the photograph, almost convinces himself that there is no mirror. Almost. This has resonance with the faked mirror-selfie (kind of). If there is no mirror, and thus a camera (unseen) taking a photograph of the trio of Wall, model and (inactive) camera then other aspects – particularly the hidden-not-hidden flashlights – become problematic. Of course, this work and other works by Wall are meticulously composed and constructed over lengthy periods of time. In fact, Wall reveals that Picture for Women is formed from two joined images, a direct take on creating artifice and disturbing the separation between depth and flatness. Crafty old Jeff.

As I tried to explain (badly) above, my feeling is that the wooden shelf is ‘faked’ via careful cropping to create an illusion like the shelf against a mirror wall, making the photograph have a magical quality such that everything exists ONLY within the mirror – there is no reality on the ‘real side’. Rectilinear pipes up high, matching tubular chairs carefully arranged as if creating an avenue of sight, bare bulbs, cables slinking diagonally across the floor, three large windowpanes squeezed perfectly into the middle section of the apparent triptych… we scour and scutinise them for further reflective clues in the vanishing points, but nothing. Everything is tightly controlled by Wall. It is a portent of the aura and era of the mirror-selfie, a photograph created in 1979 but very much for our times.

We can briefly consider another possible input to Picture for Women, the self-portrait produced by American photographer Berenice Abbott in 1928. She poses with another camera – a hulking large-format device cowed down like a tamed beast – and stares HARD into the camera that captures the image.

As with Wall’s image (and the Vivienne Westwood photoshoot by Perou) there are photographic paraphernalia and studio devices in the background, and these are called to serve in the business of illusion. An angled (and unused) spotlight clearly behind Abbott is in line with the side of her face. Yet, her face is also illuminated on this side, giving the impression that the spotlight is accomplishing this, though in the process being somewhat miniaturised. This act of reassembling the assemblage necessitates a flattening of the picture plane such as suggested by de Duve in regard to Jeff Wall. Hey, there’s even an open door just beyond the depth of the field on the left… giving us echoes of Velasquez and his much-analysed Las Meninas that cropped up in the previous post discussing Richard Hamilton.

Time to move on.