*the name for a 2-day gig in 1981 that usurped the Futurama format (that I attended)

For this post I’m momentarily jumping forward to the mid-2000s when my interest in clothing was reinvigorated. I will fill in the gaps – the periods of nothingness – in later posts, but for now this post serves a purpose as it loops back into the early 1980s. Which is where things are if we take these posts as approximately chronological. It also introduces the idea of clothing as time-travel, which is something that my writing will slowly work towards.

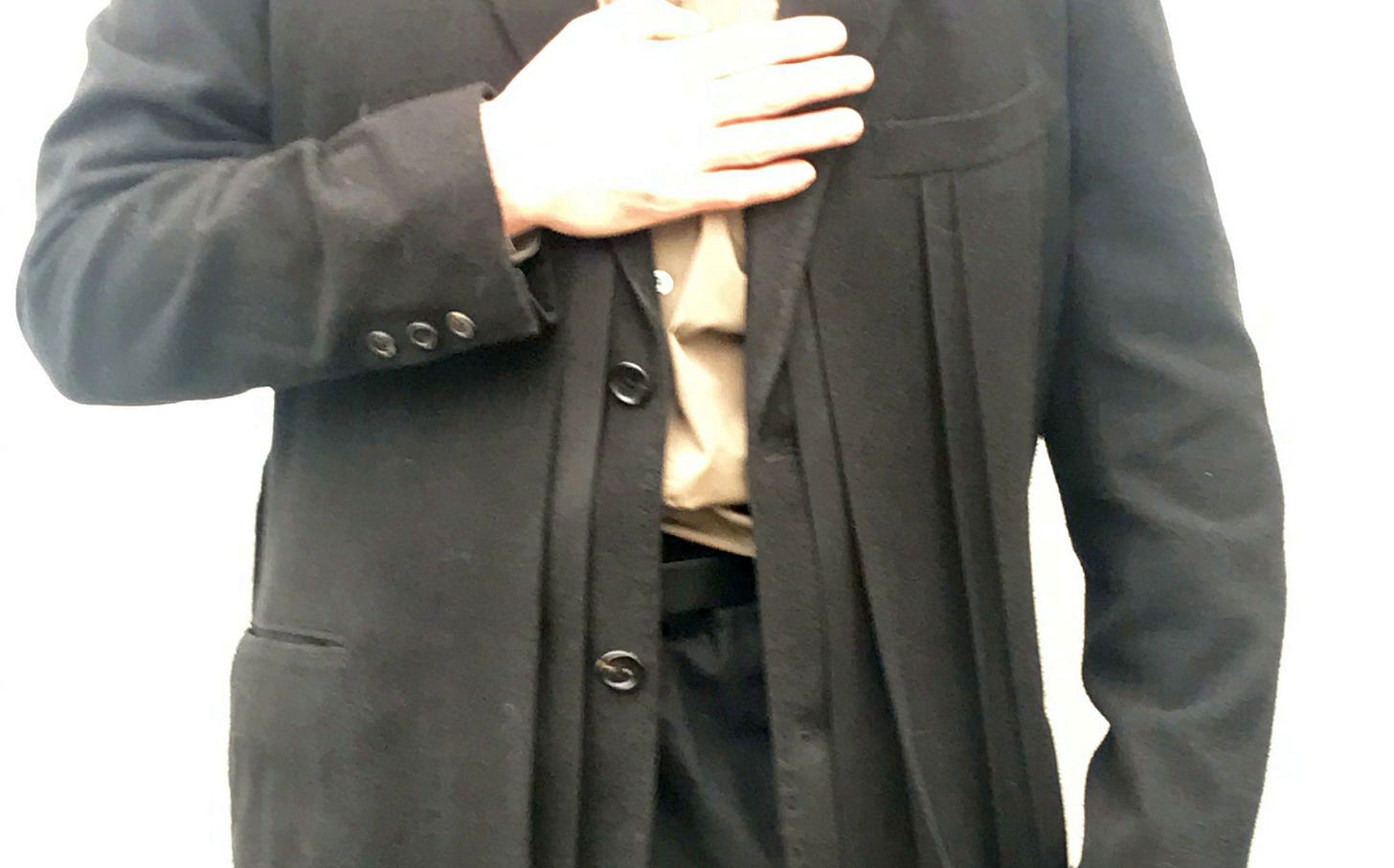

In winter 2008 I purchased a Yohji Yamamoto blazer from the (much-missed) Barnsley outlet Pollyanna. It was, once again, an incredible item by the Japanese designer. It could be described thus: made from felted wool with full-length felted silk pleats giving a concertina structuring of discreet silk folds running vertically and interspaced around the body of the jacket. But that didn’t do it justice. Description can never do Yamamoto’s work justice. I was obsessing about it from the moment I laid eyes on it.

I will have more to say about the shop Pollyanna in later posts…

One problem though… this garment also stood out for me because it was the first jacket I had seen with a four-figure retail price tag. Understandably, this was something of a shock moment for me, numbingly inevitable, as prices had been heading up year-on-year for designer clothing. By the time I purchased the last remaining jacket (by pure luck or destiny in my size) it had been substantially reduced in the sale, and I must admit that part of the drive for me to purchase it was to own something that traversed this price-point. I know that sounds ostentatious or grotesque, but it was not the primary driving intention – that remained the beauty of the jacket. However, the price of what is essentially a smart jacket heading to this astronomical figure is something that stops me in its tracks. I have kept the price tag and identity ephemera squirrelled in a box under the bed, but a bizarre Dorian Gray effect followed. The price tag faded to near-illegibility, like a ghost sign, the evidence of the sinful four-figure retail price retreating to almost-nothingness as the actual, unholy jacket lives on.

Returning once again briefly to the nine figure drawings advertising subcultural jackets for Christopher Robin (see the first SUB>SUMED post), an operation trading out of one of the quick and cheap fast fashion shops on Carnaby Street. Doing the sums, the jackets cost around £25 each, and this roughly converts to just under £100 in 2008. Nothing close to £1000, or the prices currently charged by a new breed of avant-garde designers and collaborations. Sadly, the prices of the clothing that interested me quickly started to head north of £1000 as the 2010s started, signalling the end of my involvement in this world through lack of finances and possibly self-imposed sumptuary laws.

What do you get for £1000 and upwards? Accumulated instances of feeling good when wearing it. A buzz even to see it or sense it sitting in your wardrobe (and an acute anxiety of moths and clothes beetles). A feeling of exclusivity in that I’m assured no-one else has one (actually, a quick aside here – I recently came across a picture of someone wearing my first Yamamoto jacket purchase in the 2006 book Street: The Nylon book of Global Style and it felt strangely pleasing). Comments accrued from others for looking good, glances as part of a scopophilic society of sousveillance – can I total these with a metric? Is there a point? There’s a glimpse here of the world that Brent Luvaas encounters in his 2016 ethnography of streetstyle fashion bloggers, as he details the privileged kids who are “shrouded in couture” and posting ‘fits’ for their Instagram feeds.

Back to 2008, before Instagram fits, looking ‘fire’, and teenage kids ‘dripping’ in ridiculously expensive clothing, back to a sumptuous jacket that you want to hold close to your face, to feel the softness, to take in the smell of the rich fabrics. As with all Yamamoto clothing, the jacket feels incredible to wear, a feeling that is hard to put into words. This is the designer at his scintillating best - the felted wool and silk is unbelievably soft and luxurious, and all the detailing is on the cusp of perception. The jacket glimpses its detailed structure when you move around or rotate your upper body, an example of the “sublime encryption” that the designer strives for. Yamamoto, in an interview for his recent V&A exhibition, talked about how he liked to “put air between cloth and body” and evoke the cut and feel of the “vagabond”.

There is an old and lingering argument that this clothing is designed for high-salaried middle-aged media executives with middle-age spread from liquid lunches and a cloistered radicalism mixed with bohemianism. The late and great Tony Wilson of Factory Records is given as the perfect example – he was an avid buyer of Yamamoto clothing at the Richard Creme shop in Manchester. There is also a great clip of ex NME scribe Paul Morley (and sometime Wilson protégé) discussing Twin Peaks on an October 1990 episode of BBC2’s The Late Show wearing a Yamamoto jacket with black polo-neck underneath. Typically, the feel is not too whacky but the wearer gets off on the subtle beauty and minute subversiveness of the piece. Deconstructivist phrases flow, naturally.

I am drawn to jackets that have an ability to transport me back to my teenage years of the 1980s when I was discovering clothes and trying to get the right look… trying to understand through trial and error how subcultures and clothes worked together. Writing about the meaning of clothing within subcultures often has a blind spot, driven by the late 1960s and 1970s cultural studies tradition of attaching a wider meaning (around hegemony and class resilience) to subcultural nuances of the mods, skinheads, rockers and punks. More recent work – often labelled as post-subcultural – draws more on real life experience and testimony. The intricately and academically derived meaning of clothing does not necessarily resonate with the subcultural cohorts. No surprise there. Part of the reason for seeking clothing towards a particular image is to simply look good within that subculture and so gain approval and respect from the peer group – to have enough to be both identifiably part of the subculture but also to be slightly different or ahead. A delicate balancing act. This was always the impetus or life-force of mod, and it filters through to all subcultures. I have never identified subculturally as a mod (it was something of a package deal by the time it crossed my path in 1979), but it is impossible not to acknowledge the mod blueprint of perpetually seeking out good clothing, to create and inhabit the momentary ne plus ultra. Original mods did scrimp and save to get the right clothing back in the 1960s, spending way above their station…

Perhaps here is an escape clause from ostentation? It is worth a try. The Yamamoto black jacket transported me back to my days of clipping out advertisements for Fab-Gear (later X-Clothes) from the back pages of NME and Sounds. Bizarrely, I still have these advertisements, as they obviously struck a chord above and beyond the usual advertisements that I have discussed and used in other essays. X-Clothes was soon joined by Other-Clothes, advertising in early issues of i-D, as competing shops in Leeds (with X-Clothes later expanding to Sheffield and Manchester) that were a northern gateway to the fashionable clothing from London in the early 1980s. They were a cut above the cheap and nasty Carnaby Street (Christopher Robin advertisements), and they often showcased examples of BOY, PX or Susan Clowes clothing that carried its prohibitive price north of the Watford Gap. The Yorkshire chorus of “How much?” echoes from the early 1980s like a ghostly incantation.

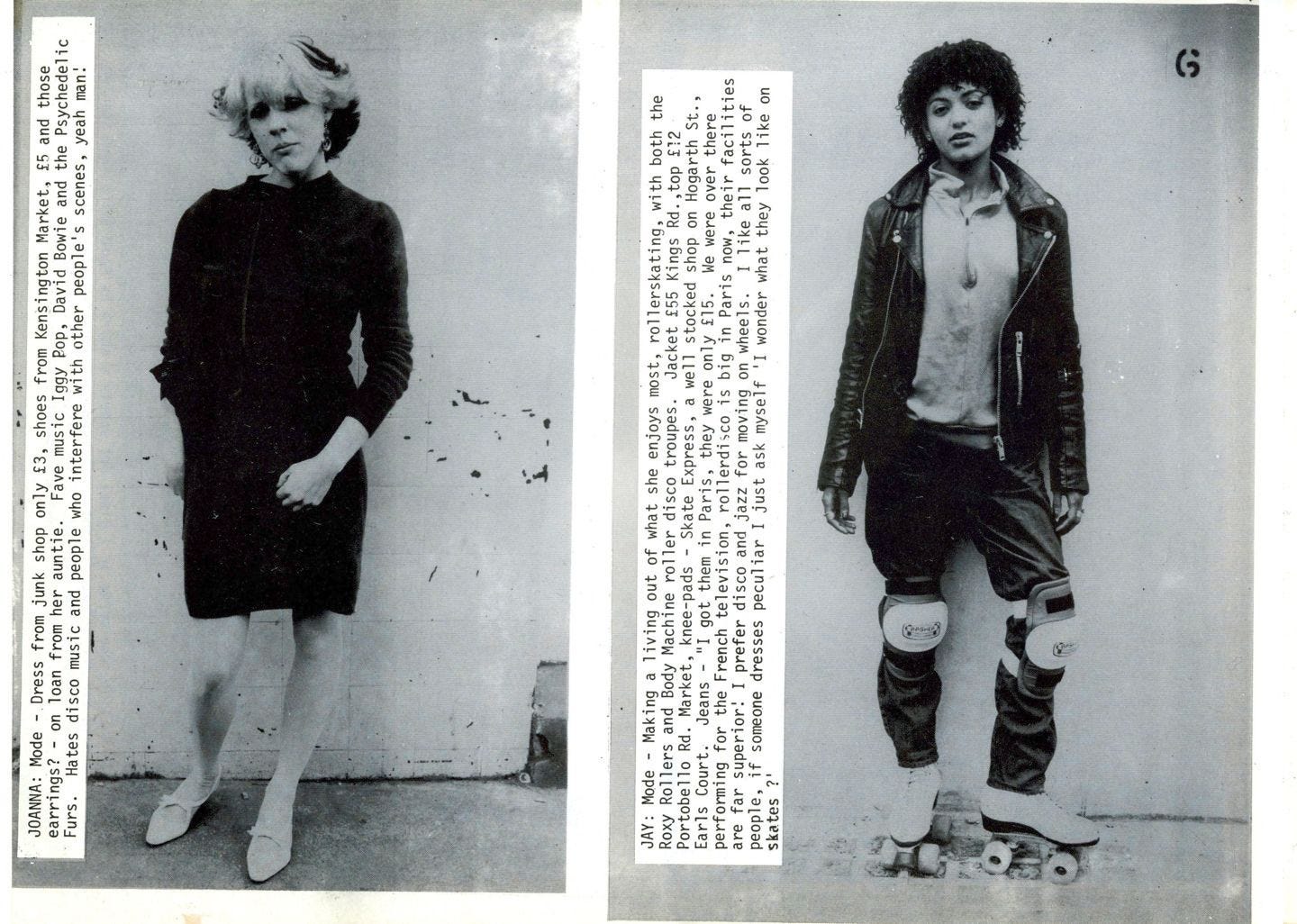

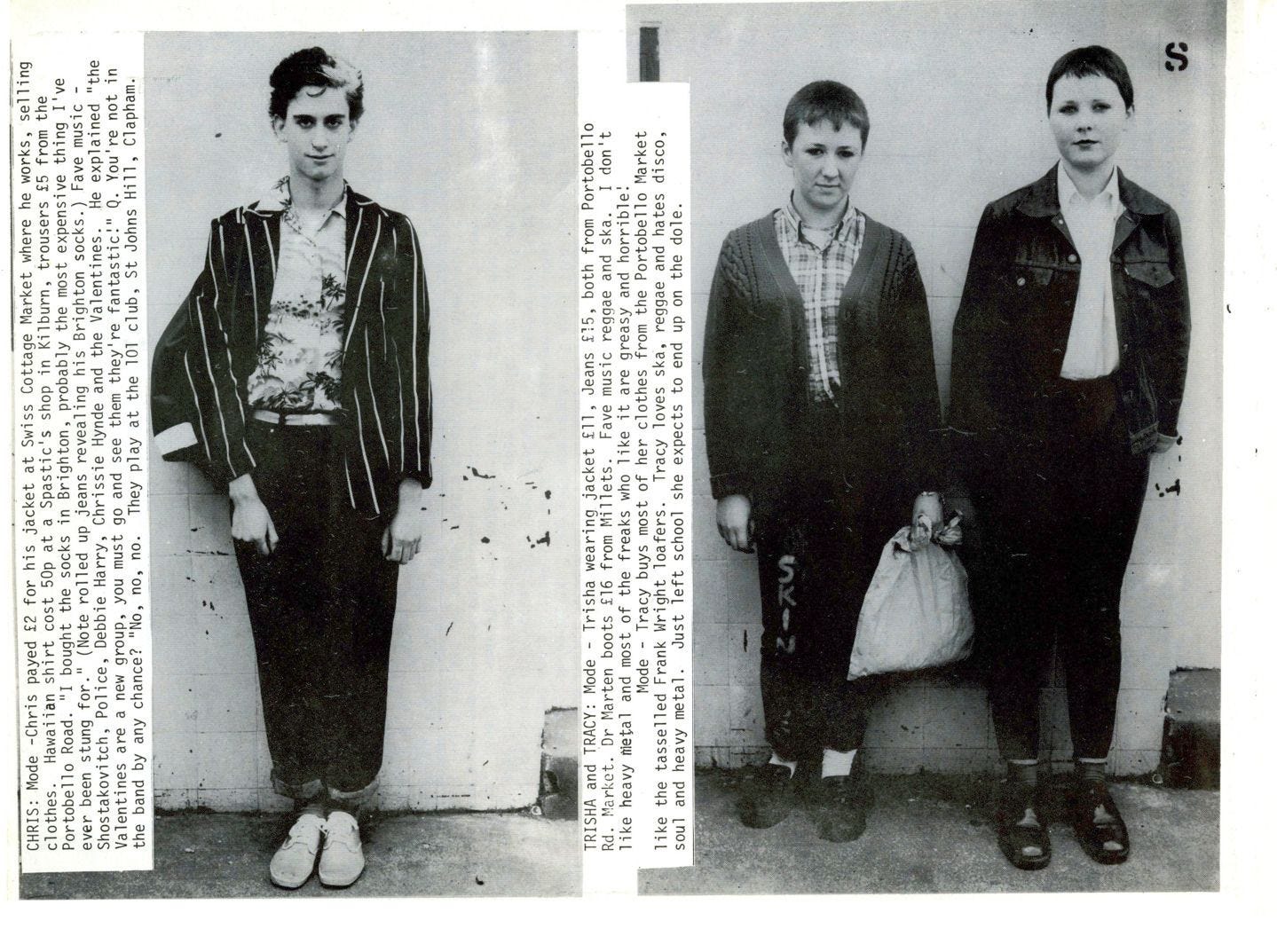

For me and my cohort, these shops were also the go-to place to buy two staple elements of subcultural dwelling: Crazy Colour hair dye and i-D magazine. I tried to buy i-D from its inception in 1980, picking up issues when we went to gigs in London, Leeds or Sheffield. It was hard to find and I still treasure my early issues. The magazine was revolutionary, conceived by Terry Jones in 1980 and running almost parallel to The Face, sharing a similar mission to stake an assured claim in the new decade. It featured the work of ‘rebel stylist’ Caroline Baker, who claims to have invented a form of streetstyle (or at least an awareness of it and attention to it) with her ground-breaking work in the late 1960s and 1970s for independent magazines such as Nova. Baker was on the one hand deconstructing fashion but on the other was constructing the reality she claimed to document, embellishing photo shoots with quirky items from outside the pre-set fashion system by dressing women in oversized second-hand menswear. Her approach informed the urgency of i-D. With its deliberately elusive nature and cut and paste layout, the magazine felt more attuned to the street with a fanzine like immediacy and remit – what Catherine McDermott in her book Street Style labels as “anarchic panache”.

Key to its attraction, for me, was the landscape layout; this was unusual (possibly unique) for such magazines and had a pleasing resonance with the PG Tips card albums of the time that I had meticulously collected through childhood. That intoxicating sensory connection between smell, texture and the sequence. This might sound a strange thing to say, but the segmented layout of including rows of evenly-sized photographs of ‘normal’ abnormal people (punks, new romantics, rockabillies) felt like you were perusing an album of football stickers. The magazine was revolutionary in many senses, having a back-history to a project by Jones whilst working for Vogue: he got together with Carlisle-born photographer Steve Johnston to photograph the early onset of punks on London’s King’s Road. Johnston employed the technique of fixing on one spot, with the white wall background, and creating the straight-up. The project was, unsurprisingly, too ambitious and left-field for Vogue, and it emerged instead as the one-off publication Not Another Punk! Book In 1978. This set the template for the early issues of i-D, the landscape portrait said to evoke the spatial feeling of the street and the regimented photographs with a strict neutral gaze resembled what Jones describes as “sartorial police files”.

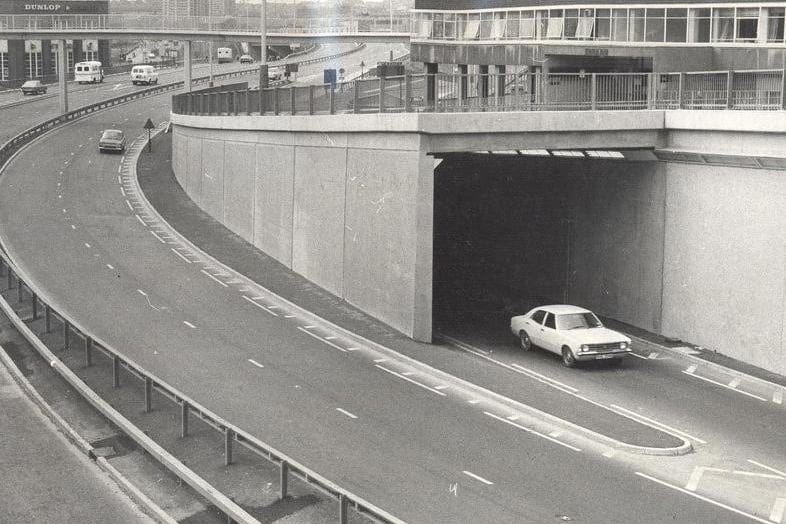

Returning to the clipped advertisements, I never actually sent off for anything because I still didn’t trust what I couldn’t see and hold, but in my early days of travelling to Leeds and Sheffield for gigs I used to visit the shops as a priority and try and get something affordable. In the early 1980s journeys to and from Leeds had a lasting and unique character – hitching up the M1 motorway with the expanse of concrete snaking left then right as it deposited you right in the heart of the city. Likewise, when it was time to come home, the M1 literally started with a lay-by on the southern edge of the city centre amidst depots, breweries and warehouses. A waft of hops, diesel fumes, grime. More smell associations to haunt me through later life.

The Leeds X-Clothes shop was on Call Lane, a curved road that slowly dropped out of the city centre, flanked by brick railway viaducts. A perfect road for an alternative shop. Dark and seemingly dangerous, it was also the road leading to Leeds Queens Hall, the venue of the legendary Futurama Festivals that supposedly brought together a post-punk interpretation of possible futures. Thus, it was associated for me with exciting times, punk and post-punk gatherings, sleeping on unforgiving floors, running the gauntlet of infamous Leeds football firms, right-wing nutcases, skinheads and general Tetley-drinking bully-boys. Leeds had all of them and more, an endless supply on tap. Watch your accent, hide your hairstyle, stay alert.

At the Futurama events you slept on the concrete floor, or at least tried to amidst the general noise, chaos and cold – the overnight stay of Futurama is a rite of passage. Leather jackets, army surplus, 1950s grandad coats - your outer layer served as either an unsuitable mattress to lie on or an approximate blanket to keep warm, so what you wore was subjected to scrapes, creases, stains and smells. There was also the scuzzy surface awash with grotty fluids… half-full cans of lager kicked flying as people stumbled around in the dark through the early hours of the morning. The Yamamoto jacket and its four-figure price could never be subjected to such teenage rituals. The thought of it gives me palpitations.

The advertisements for Fab-Gear were obviously tuned into the subcultural strands of the early 1980s, and they generally employed photographs of the clothes being modelled rather than the untrustworthy drawings utilised by their competitors. The photographs were predominantly cut-out silhouettes and arranged like a child’s dressing-up game, the heads of the models removed. I’m not sure why, maybe new romantic haircuts hadn’t made it north in 1980 or 1981. One example stands apart, a great image of an asymmetric haircut unfortunately spoilt by the model wearing a dreadful cape and frilled shirt, framed in a gothic arch. It is from March 1981, before the days that Leeds became a goth stronghold, giving the clipping something of an incunabula status. If you look closely you can see the template for the jodhpurs that I attempted make for my own new romantic outfit.

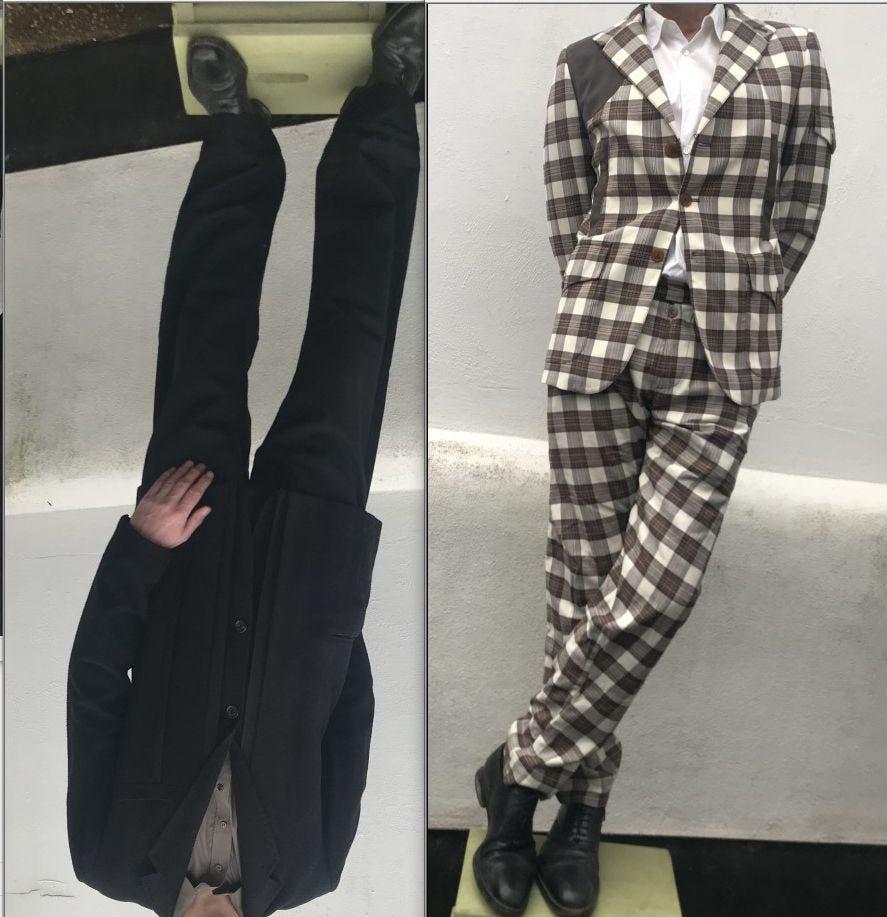

There is also a suit jacket advertisement, from February 1981, arranged like a court card in a standard playing card deck with the figure both upside and downside. The advertisement has a tartan suit one way up and a cropped style new romantic suit the other way. Like the portrait of Animal Nightlife (see forthcoming essay for this reference), this image has stayed with me for 40 years, another fashion chronotope. It had an element of early PiL – John Lydon – who dressed so well. Those suits looked so good. However, what struck me about the 2008 Yamamoto jacket was the similarity with the Fab-Gear suits. I even had a tartan suit that could complete the pairing, and so a recreation of the photograph was the least I could do to embrace the hauntological calling. A life, or a possible life, now complete.