Thinking again about the coachman coat and the Amazon derivative, and trying to articulate my dismay / horror / shame / etc. Some deviations through pop culture and quick-fix half-baked academia. Please take these with a pinch of salt, if indeed you take them at all. Normal service resumed next time with the third and final coat in the HG3 trilogy.

Bomb culture

A first divergence. The track ‘Big A Little A’ by anarcho-punk band Crass was the flipside to the 1980 single ‘Nagasaki Nightmare’. It is often discussed as a touchstone of their individualist anti-state politics. The track commences with the couplet:

Big A, Little A, Bouncing B

The system might get you but it won’t get me

It references the all-encompassing bogeyman of “the system” and how you should choose and strive to live free from it. Crass vocalist Steve Ignorant, who continues to tour with various Crass compositions, quotes the track as having such significance. The writer of the lyrics – Penny Rimbaud – suggests another layer: “Steve brought the wisdom of the street into my life so we could talk in a very balanced way. I could talk about another part of society and use a privileged education against privileged education.” This is his nice way of saying how class backgrounds co-existed within the Crass collective and, at times, formed the subjective content of their invective.

On hearing and purchasing the record in 1980 I assumed that the big A and little A related to atomic bomb variants and the bouncing b was another bomb (the bouncing type, of Dambusters fame). This was because I assumed it synchronised with the lead track ‘Nagasaki Nightmare’ which clearly related to the proliferation of nuclear arms and the sheer stupidity of mutually assured destruction. It was a typical Crass package with a fold-out sleeve of intensely detailed polemic and an anarcho-pacifist patch for your jacket. The track was revisited in 1984 with the release ‘You’re Already Dead’, which I coincidentally lifted to title my goth writings on the earlier SUB>SUMED post. It REALLY felt like the world was on the verge of destroying itself, a bit like the current era.

I realise now that the initial rhyme of ‘Big A Little A’ comes from a children’s game where for each line of the rhyme you progress through making a big shape with your hands, followed by a little shape, then an arm bouncing motion, and then a ‘peek-a-boo’ as the fourth line of the rhyme offers a number of scenarios such as “Cat's in the cupboard and can't see me” or “Baby is hiding and can't see me” etc. It should have been obvious as Crass sample the rhyme with children laughing, repeating the sequence for the first 20 seconds of the track. I guess I didn’t listen to it too closely, and the music of Crass is something I seldom, if at all, revisit.

The gentle rhyme soon gives way to a stark guitar non-chord which approximates to a punk accompaniment to the rhyme itself. The children can still be heard in the background. Then it speeds up and Steve Ignorant intones the rhyme in his rasping voice, dramatically diverging on the fourth line to set the anti-system tone. The track then pauses in the punk-rock handbrake style, Ignorant counts forward to seemingly break the gentle hiatus of temporality that a children’s rhyme evokes, and then the whole thing takes on a thunderous and urgent pace as the anti-system lyrics are blurted out:

External control are you gonna let them get you?

Do you wanna be a prisoner in the boundaries they set you?

Punk academic Paul Frost has expertly dissected the track as part of her dissertation, and it is included in a Louder Than War post here. Frost turns more to examine it as a composition, citing various jazz and avant-garde influences (such as John Cage) that informed Penny Rimbaud’s thinking and background at the time. Perhaps there’s something else in the lyrics that reaches back into his liberal intellectualism?

The repeatable games such as ‘Big A Little A’ are used by Freud as an analogy/thinking tool when he introduces the “fort-da” exclamation as a footnote. It is apparently Freud’s grandson getting giddy at a cotton reel being repeatedly hidden and revealed (fort-da = gone-there) that grabs his attention. Of course, Freud being Freud, links this to various ideas about missing mothers and sexual organs (Crass borrowed from Freud – or more so critiqued him – with the album Penis Envy). I do not think there is a Freudian angle to Penny Rimbaud’s use of the ‘Big A Little A’ rhyme, but it throws up another intriguing angle…

French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who set out to realise and supress Freud, introduced the theory of ‘the other’ – or l’autre – to compound Freud’s understanding of the other as simply (an)other person. Lacan wanted to bring in Hegel, via Alexandre Kojève, and have a mathematical tension and binary dialectic. He thus proposed a ‘big other’ (big A) and a little other (little a). The little other is not really an other, but a reflection/projection of the ego – a specular image – whilst the big Other is radical alterity, the symbolic order, the socio-cultural environment of norms we are born into.

Is the Amazon coat, and the world it inhabits, the big A or little a of my own ego? It feels like both at the same time. Part of me wants it to be different, for my image of myself in my haute-goth coachman coat to somehow be a rejection of the norms of the ‘supermarket of style’. But this supermarket of style is Lacan’s big Other, something that is inscribed and inescapable…

Is it what it is?

A second diversion. Step back, breathe deep, and try to gain some sanity and a vestimentary foothold. Subcultural engagement involves a kinship of dressing up and acting out. This is the baseline of a fashion – a prescribed way of dressing, with objects, rules and codes. It’s what we did, what we do.

A diachronic reading of subcultural fashion, and of goth in particular, invites two immediate methodological devices; authenticity and the emergence of style over fashion. We associate our subcultural time (my early 1980s time with punk, goth and other niche scenes) with authenticity, an authenticity inevitably measured against the perceived accelerating inauthenticity of subcultures after our time (grumpy old git syndrome).

Critical theorist Walter Benjamin’s landmark essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ suggests that aura and authenticity are inseparable, and the argument follows that the aura cannot exist with a subcultural identity pursued through Polhemus’ aforementioned supermarket of style. Not that Benjamin and his snobbish Frankfurt School theorists had much time for any popular culture. I delineate the Amazon-available coachman coat with its gothic prolix from my subcultural purview – but, as we know, goth persists and sticks.

An argument can be put forward that after the engaging in a subculture through fashion, a sense of style can follow as a kind of aftertaste and impetus. Subcultures and their look provide an energy and purpose, but you move on from them. What remains is the buzz of looking good, standing out, making the effort, making people look twice in envy or disgust (or both). Some elements of the post new romantic crowd embodied this the most – spending the early 1980s as part of an ultra-dressy subculture and then looking for the buzz of great clothing without prescribing to a never-ending nightclub scene of dressing up in pyjamas or obscure military uniforms. Of course, people like Leigh Bowery, Trojan and their immediate crowd were the exception. We saw this urge for a post-subcultural but still ‘authentic’ look and style with the gradual encroachment and embracing of Comme and Yamamoto in The Face, Blitz and i-D. The birth of the next generation of pure style magazines such as Arena in the later 1980s signalled the rise of this tendency.

Goth, however, takes a different path: its persistence of fostering allegiance and its recalcitrance to calling time on itself, this constant renewal like no other subculture, blurs the distinctions as authenticity struggles against inauthenticity, and style is always-again subsumed into fashion. A fashion that dissolves all boundaries of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, encompassing the gothic-influenced high-end and the clickable off-the-peg Amazon outfit. The haute-goth of Vivienne Westwood or Rick Owens is brazenly stared down by the latter Amazon identity, exerting a pull on the persistent gothic style – the process of interpellation defined by Marxist thinker Louis Althusser in which the call to the subject of “hey you” evokes a turn of the head in acknowledgement and a muttering of “who, me?”. Yes, the Amazon goth is calling me.

Haunting vs hauntology

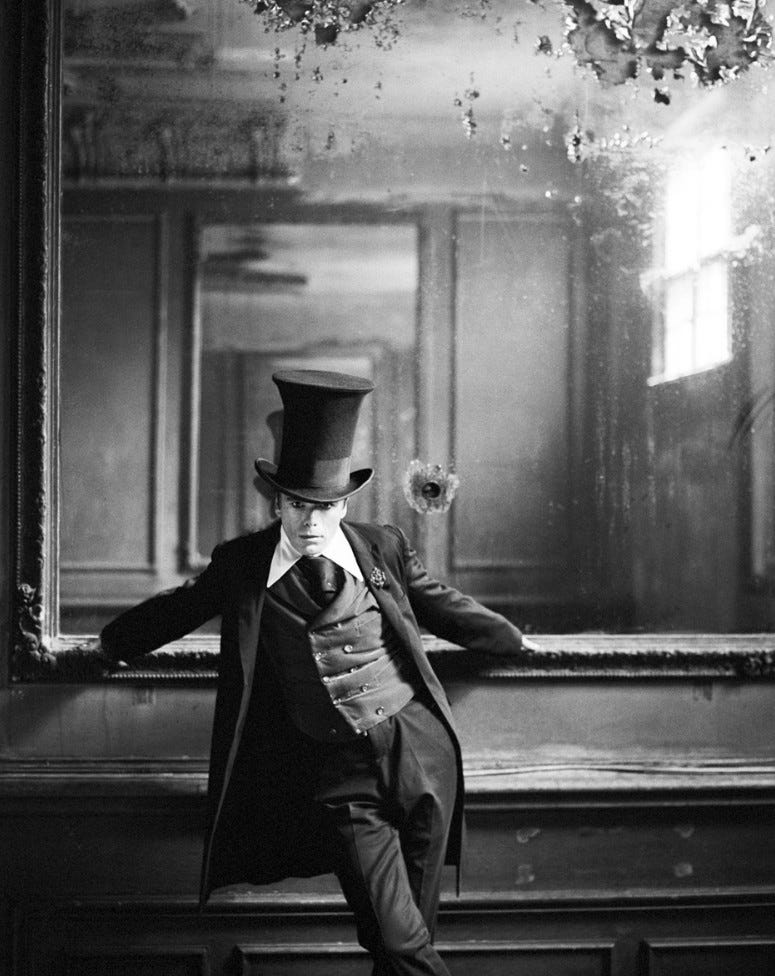

So, I need to switch away from goth, to talk myself into the beauty of THIS coat here, this Vivienne Westwood wool coat that fits to the body with long slit pockets and a cutaway shape. It’s a thrill to wear it – the rough fabric smells of rich wool and the cuts and darts pull the coat in to a position of mocking class and formalism. The cutlass-shaped rough-hewn neck choker, when fastened up, applies the finishing touch of vagabondage, and the hip pockets are deep and inviting for stowing all sorts within. The seams are visibly raw to counteract the formal connotations of the coat. The lining is a silked cotton with an intricate tessellated pattern made from cutlass icons rotating through ninety degrees.

It captures an imaginary punk glamour that Westwood conjures, the bi-stable illusion between an invite to a formal occasion and an urchin with ulterior motives (and deep pockets). This infiltrated and corrupted decadence informed a current of her work in the new millennium, strangely antagonistic to her more visible practico-activist stance on environmental and political justice issues such as anti-fracking. As the 2010s progressed she even tag-lined her collections with the phrase “Buy Less, Choose Well, Make it Last”. She could afford to make such gestures, knowing she had a diehard following who collected as much as possible every season!

As a final gesture, we can attach a little more high-end academic attachment to this garment. I have already used Jacques Derrida’s concept of hauntology, but we can apply it again here. As with all of Derrida’s work it is archly conceptual and slippery to grasp, concerning an ontology and taxonomy of ghosts, revenants and spirits that haunt literature and politics in various ways and for various motives. Hauntology was simplified and, in turn, became subsumed by this simplification. Most philosophers would probably bridle at their ideas being dumbed-down and consistently misapplied, but you feel that Derrida would have found this amusing. Hauntology is now understood simply as something from the past that premised a future, but the future has never come to bear as the ‘something’ from the past was cut down and extinguished. This was previously known as retrofuturism, before it was consumed by academia. The tangible-intangible presence of hauntology is the remnant of a possible future from the past coexisting with the present – the “time out of joint” that Derrida borrowed from Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

You may ask: how does that fit here? In the early 1980s the decadence of new romantic fashion outerwear – think capes and tailcoats - and the scruffy charity-shop raincoats of post-punk simultaneously occupied diametric poles of fashion connotation and indexicality. In a clever reversal of hauntology, Westwood brings to bear a present that invites us to imagine a different subcultural past, rather than evoking a past that invites us to consider an alternative present that can linger alongside the drone of the everyday unpicking its hegemonic seams.

It is an interesting juxtaposition of methodologies, in that Westwood and her partner McLaren set out working with Teddy boy clothes that had cross-class roots in plundering the clothing of the Edwardian dandy into the rough and ready street culture of 1950s gangs, swagger and violence. Again, subcultural time out of joint. Of course, the pair were providing clothing to a like-for-like regurgitated subculture of Teddy boy at the start of the 1970s. Subcultural timeframes slip and overlap, and are creatively reimagined (and then derailed) by provocateurs such as McLaren and Westwood.

And, in a broader sense, this reversed hauntology applies to goth in the sense of how I have approached it in these essays. It persists in the now as a subcultural and fashion force, but we variously and creatively fabulate a backstory that fits our whims and motivations to appear as owning authoritative knowledge. Nearly there now, we just have to poke the ghost of nihilism that we briefly disturbed when discussing the Rick Owens black coat…