A recap and a signpost

Parts 1 and 2 introduced the first haute-goth coat (by Rick Owens) and set out some framework to explore the lacuna in goth in the early 1990s and rapid rise a few years later (which introduced the nascent concept of the gothic haute couture via designers such as McQueen). This next section revisits my earlier essay to pick up the threads of 1983 and 1984 when a goth sound and look emerged in both northern England and on the post-punk circuit of following bands around the country. Goth fashion in this time, as with other contemporaneous subcultures, was never driven by expensive labels, and seldom by specialist labels at all. It borrowed from second-wave punk, psychobilly, anarcho-punk and a bit of second-hand glam with frilled shirts and purple nylon if that took your fancy. As gothic historian and theorist Catherine Spooner correctly recounts in her 2004 book Fashioning Gothic Bodies, it was a distillation of a look drawing from punk, fetish elements, and a “graveyard exoticism”.

As she often does, Spooner gets it right here, emphasising the more nebulous nature of goth fashion. Spooner’s work resides in contrast to other goth texts such as Valerie Steele and Jennifer Park’s lavish 2008 book Gothic: Dark Glamour which stresses that there was something more organised (and thus continuous) towards a goth subculture in post-punk 1979. To suggest that figures like Dave Vanian of The Damned spearheaded a goth movement is, in my opinion, simply wrong – The Damned were a theatrical pop-punk band and the lead singer had a novelty (gothic) image that was not replicated by the band’s fans. The band were not full-on goth until the 1985 release of ‘Grimly Fiendish’, co-written with Dr and the Medics who then managed to get a novelty goth-psychedelic crossover hit of their own with ‘Spirit in the Sky’ in 1986. This is a couple of years after the naming of goth as a subculture. The Damned capitalised on this popularity by recording the Phantasmagoria LP in summer 1985, followed by the single ‘Eloise’ in 1986. This 1986 chart-assault of ‘Spirit in the Sky’ and ‘Eloise’ was a MAINSTREAM goth moment (even if we give credit to Vanian’s partner opening the shop Symphony of Shadows in Kensington’s Hyper Hyper in 1983). Similarly with Bauhaus; even though they made an astounding entry onto the scene with their extended debut single ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ (which would be claimed as a goth anthem), they also experimented with different looks and sounds in their early years.

Another 1980s goth

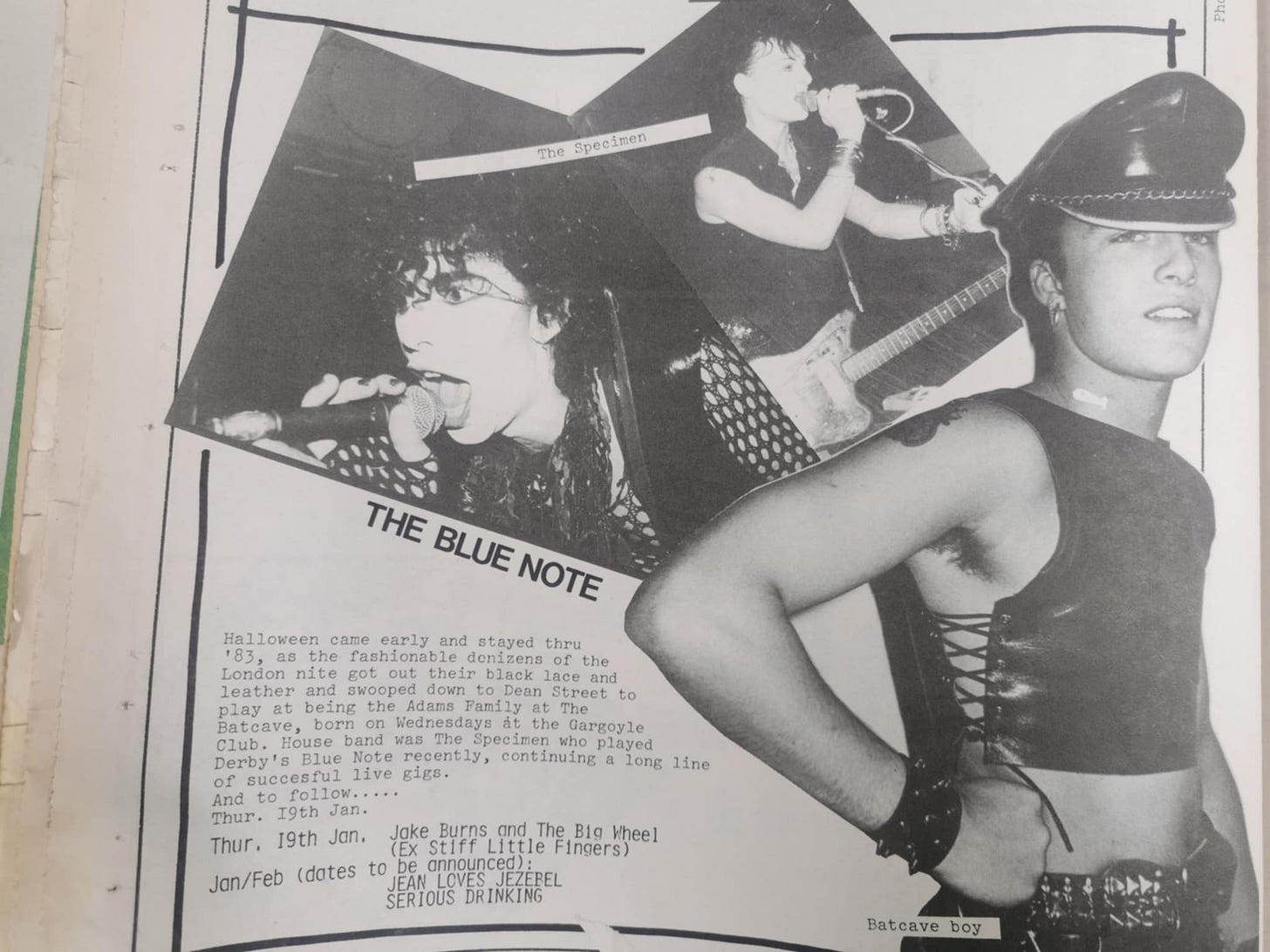

If we are thus tackling goth here as a fashion moment, then it is important to note that there was a fashionable instance of what we now call goth with the opening of London’s Batcave club in July 1982, coming with an associated feature in The Face. Understandably, this is now often quoted as either an origin point of goth or at least a singular moment it first cohered into a wider fan-based subcultural look – since the subcultural term goth was still a good year away from gaining common parlance in the music press. Specimen and the Batcave phenomenon had a year or so in the headlines, and even paid a visit to my home town of Derby. You get an idea of this in the image below, describing Specimen and Flesh For Lulu playing Derby’s Blue Note in October 1983, and showing a prominent image of a “Batcave Boy”.

The Batcave goth look was a brief time in the limelight as part of the post new romantic scenes shifting like a restless ocean. The Batcave club took place in the upstairs section of 69 Dean Street (Gargoyle was upstairs, Billys was downstairs), an iconic venue in the development of London clubbing in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The new romantic element is strengthened by the involvement of Stephane Raynor, who produced the first commercial goth/Batcave clothing in early 1983. So we now have a parallel goth look, something very specific and constructed, that ran alongside the more workaday ‘evolved’ look that was nurtured with the various touring bands and clubs in places like Leeds.

Raynor has an incredibly important role in British subcultural fashion, working with partner John Krivine at the coalface of the nascent punk scene in King’s Road. His life is covered in the 2018 coffee table book All About the Boy, though Raynor passed away three years after the publication. The book is big, bold and boastful, a disjointed roller-coaster ride through the life of a subcultural maestro who plays fast and loose with events and their chronology! There is a start point: his ACME brand, a kind of proto-punk soul-boy deviation, which was then relaunched as a purer punk style in 1976 as BOY. Raynor then departed BOY to set up the shop and brand PX as a key reference point to London’s emergent new romantic scene, before returning to BOY to explore where punk might go next.

His verdict was the horror-fetish look that personified the Batcave scene, and he utilised the strong looks of Fenland incomer Jonny Slut – Batcave regular and member of the house band Specimen – to model the new clothes. BOY ran a pincer assault of reworked Seditionaries clothes with this new goth line, taking out half-page advertisements in i-D magazine (#14 autumn 1983) with the louche Jonny reclining splendidly in the frame with his now gothic-trademark death-hawk haircut, theatrical-white pallor and BOY clothing that looked like melted cheese made of black rubber and leather draped over fishnet tights. It doesn’t take much visual analysis to see that this Batcave incarnation of the goth look was very much biased towards the fetish element in Catherine Spooner’s distillation theory.

Kink

As an aside, it is worth noting that this fetish angle runs through many subcultures, most notably punk and the precursor with McLaren and Westwood’s rebranding of 430 King’s Road to Sex between the years of 1974 and 1976. The shop sold fetish and bondage wear, encompassing pure items and hybrid items that combined elements of their previous guise peddling mutant rock and roll garments. Even as they moved forward to a more overt punk blueprint with Seditionaries, elements of transgressive sex and gay pin-up culture (Tom of Finland etc) informed their designs and prints with the infamous ‘cowboys’ tee-shirt being a prime example of overt hyper-homosexual imagery. It became a classic design because it courted so much trouble, rather than uniformly signalling the fetishistic intent or sexual proclivity of the wearer. Cultural researcher and biographer of McLaren, Paul Gorman, has forensically documented this imagery, tracking sources to obscure gay publications.

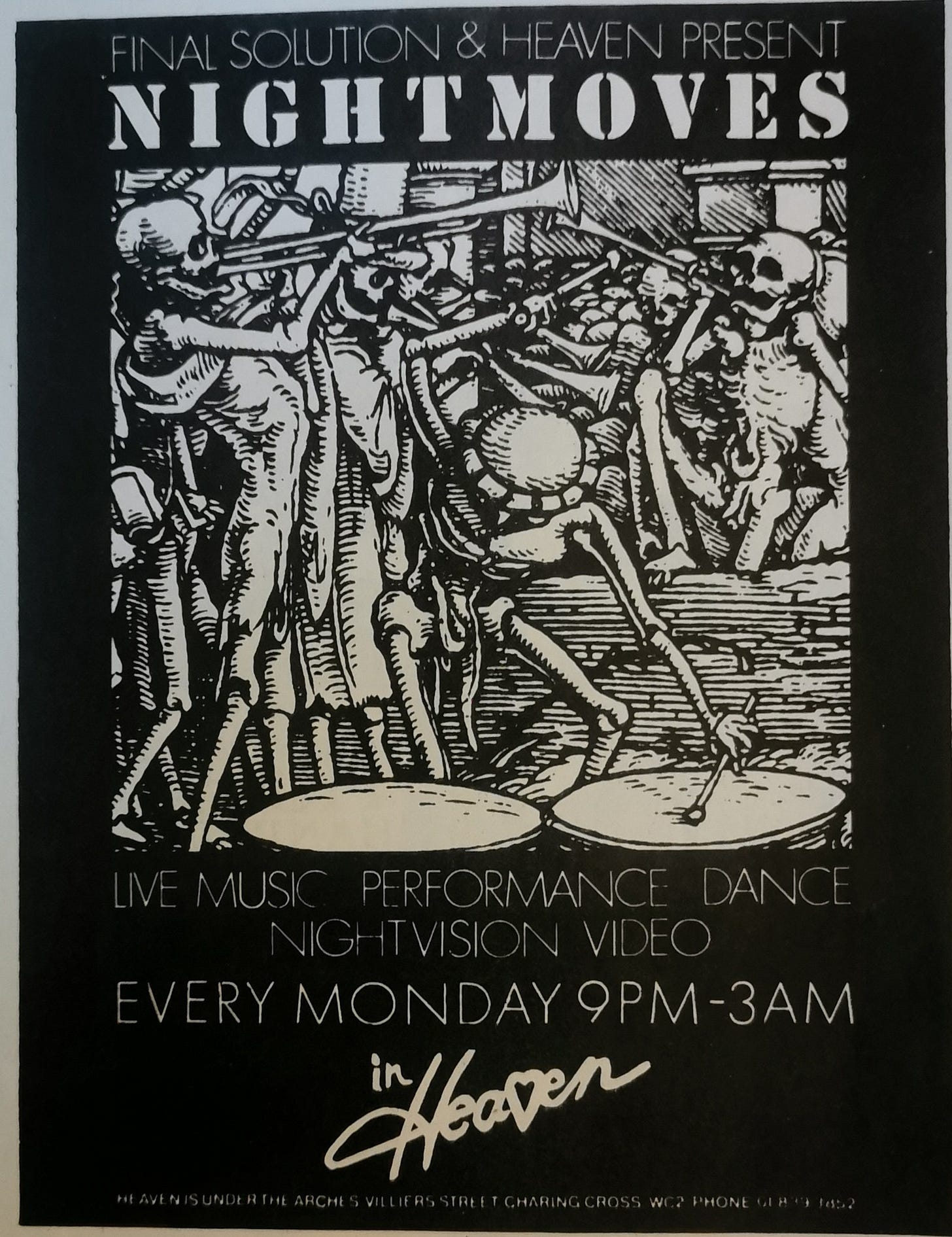

Meanwhile, a gay subculture ran parallel to the early 1980s subcultures of my youth. You can glimpse this with the September 1981 flyer for ‘Night Moves’, a gothic-ascribed post-punk night at the key gay club Heaven in London. Skeletons beat out a ritual beat and the organiser – Final Solution – were prime movers in the proto-industrial scene with bands like Throbbing Gristle. Industrial and early goth were distinct scenes but would merge in the 1990s. Night Moves showcased bands like Bauhaus away from the grotty circuit of punk clubs like Birmingham’s Tin Can or Retford Porterhouse, allowing a more theatrical presentation and branding a fetishistic goth strand in the early days that coexisted uneasily with the northern doom-punk version.

The punk crowd I knocked around with in my early years in Derby ran alongside a small gay scene, both subcultures sharing a sense of being prey to more mainstream cultures who saw a strict itinerary of drinking, after hours clubbing and punch-ups as their masculine domain. At times my punk crowd merged with gay friends to seek refuge in gay clubs or function rooms at the back of pubs. On several occasions I spectated upon S&M fashion shows which didn’t leave any fashion-positive or sexually-inquisitive impression upon me, even though some of the specific details of clamps and clips have left an indelible impression in my memory. There seemed to be a tired script to these events, with a camp compere and a succession of hapless models bedecked in gimp masks and leather vests, submitted to various tweaks and minor instances of sexual torture as a kind of demonstration of purchasable wares. The start of each show was usually fanfared by a hiatus in the hi-energy disco and the playing of a scratchy copy of Florrie Forde’s music hall smash ‘Hold Your Hand Out Naughty Boy’. Hearing this now still strikes a small chord of fear in me.

The Batcave’s alternative

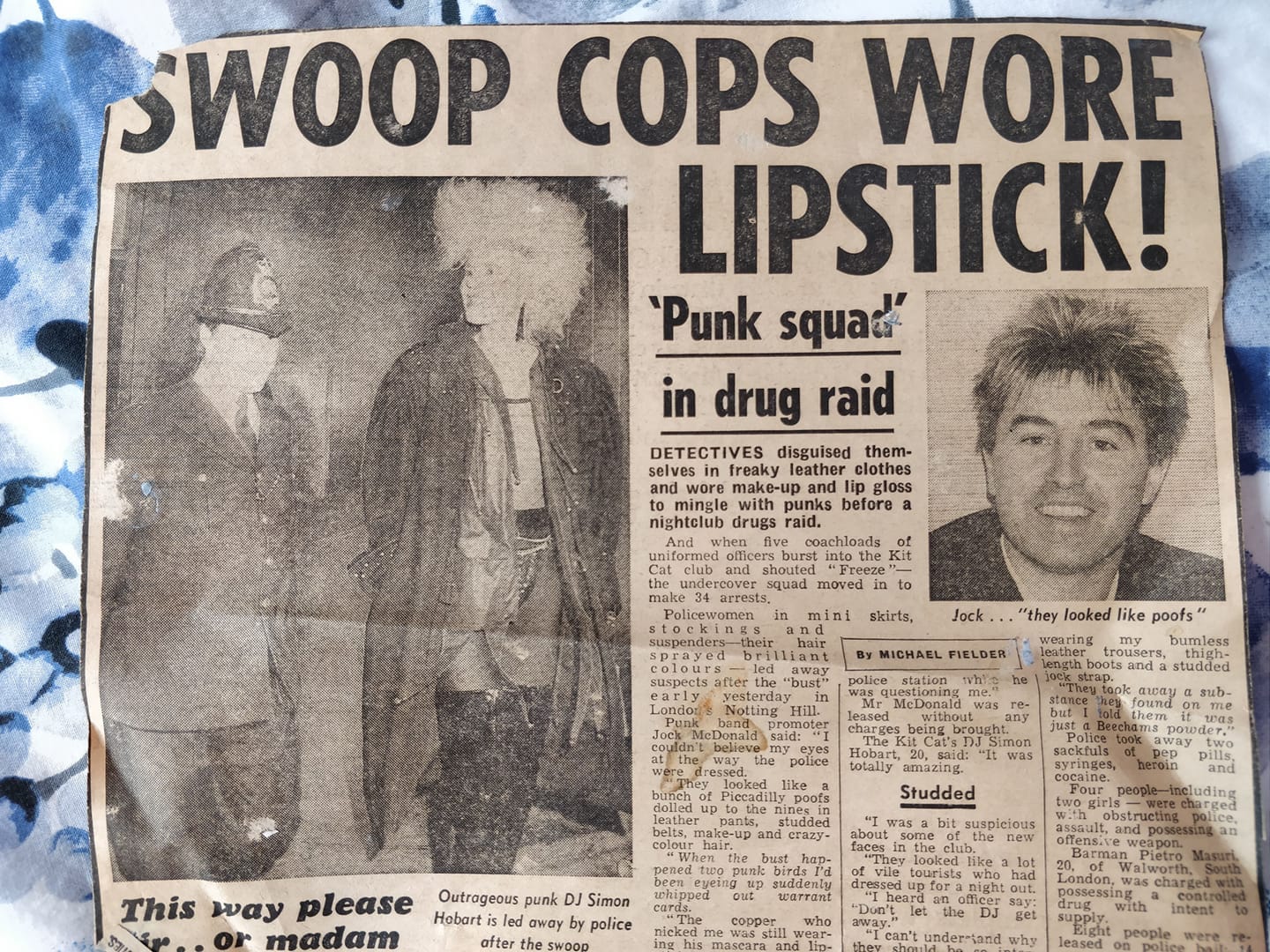

The London-centred shift of ‘the cult with no name’ to embrace an OTT fetish-gothic look via Night Moves and the Batcave was also fostered at the Kit-Kat club at Fouberts through 1984, with the organiser Simon Hobart then taking the club into a converted warehouse Pleasure Dive on Westbourne Grove for some blues party style all-nighters. Hobart was a Blitz youngster who briefly opened a club Fly Trap in June 1983 before striking a popular chord with Kit-Kat. He apparently also had an involvement with Red Lipstique’s 1982 cover of the camp-disco-glam track ‘Drac’s Back’.

His Kit-Kat club had an unexpected longevity, and acted as a goth enclave through to the end of the decade. It closed in 1989 as Hobart began new ventures, indicating how the subculture had started to dwindle as the 1980s drew to a close. Hobart celebrated the gay and dressy scene, and so quickly nurtured a crowd who had been visiting clubs like Heaven and wanted to add a bit of fetish/horror to their nocturnal wardrobe. By 1984 the subcultural term goth is in use, although the culture of Kit-Kat is still partly attuned to dressing up to shock – it’s part fashion tribe part musical tribe. The club and Hobart famously made the pages of The Sun on 21 January 1985 following a raid on the club when male and female officers went undercover as fetish vamps. Apparently there is a cover headline of the ‘Godfather of Goth’, though I have not sourced this as yet, and it could well be a piece of mythology.

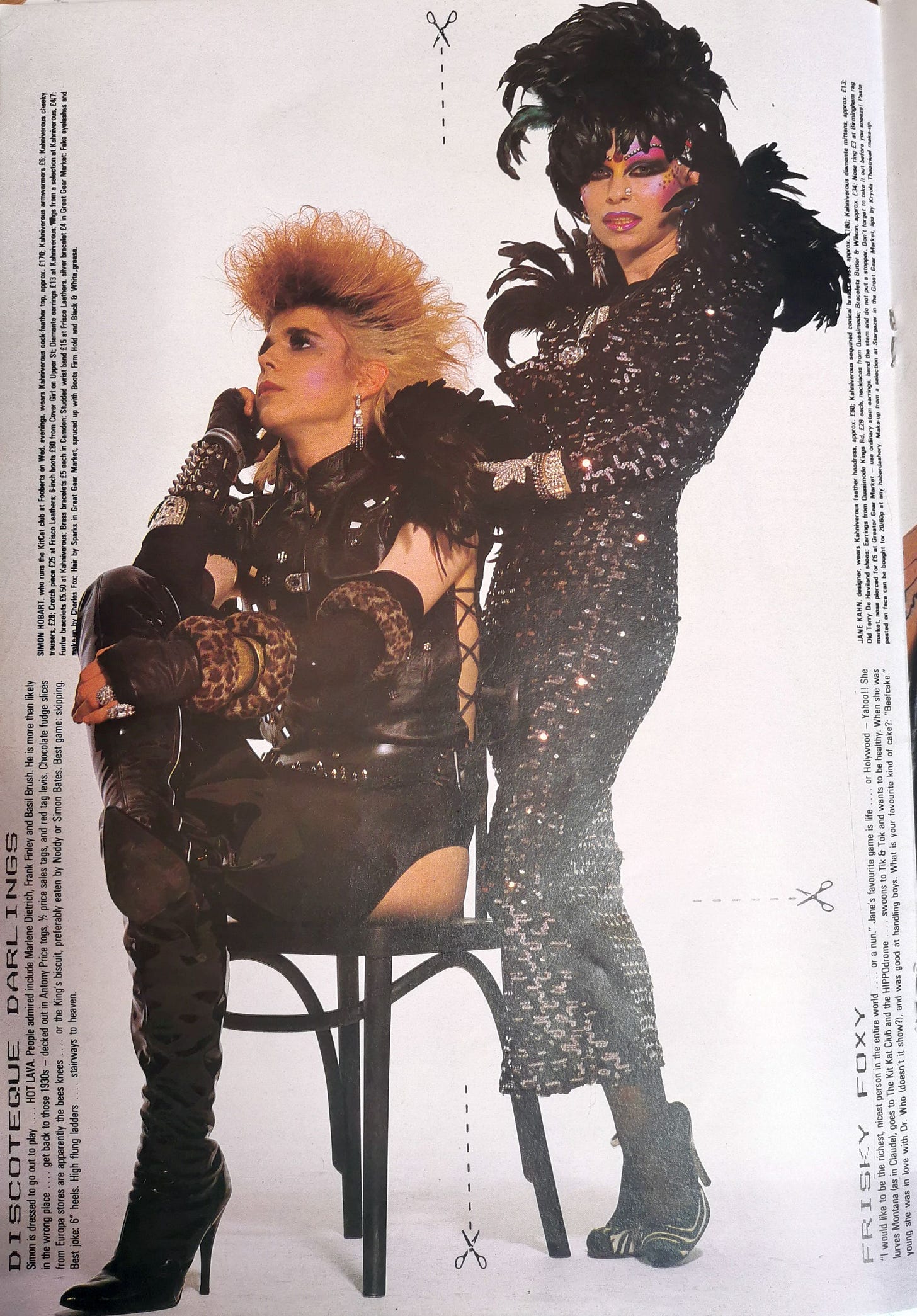

Hobart is approximately bonded to new romantic pioneer Jane Kahn, the streetstyle fashion designer from Birmingham who originally dressed Duran Duran with her Kahn & Bell label. The Birmingham new romantic scene was pretty much an advance guard, with Kahn, Patti Bell and the ever-industrious Martin Degville with his Dispensary outlet that briefly drew Boy George to Birmingham. Kahn moved to London and produced new clothes under the Kahniverous label. She is featured on the front cover of i-D for November 1984, her face close up and performing the obligatory wink.

Inside, amidst a wider feature on a whole host of post-new romantic London designers, she is stood with Hobart wearing a goth take on new romantic glam as befitting her new label. Hobart (who is running Kit-Kat at Fouberts at the time of the article) has a distinctive look that encapsulates this BDSM-derived proto-goth fashion: towering backcombed hair, studded gauntlets and leather-thonged vest, peek-a-boo PVC trousers with a crotch piece accessory, and high-heel boots. It’s a dressy and glam goth-inspired look, but not the run of the mill goth as we knew it at the time. Or, to put it another way, you wouldn’t see such a get-up chicken dancing down the front of a Play Dead gig. Strangely, it’s a look that would fit well with contemporary Rick Owens world of goth-glam.

Towards the end of the first phase

Even though the glam/fetish strand of goth re-emerged in the 1990s (as per Spooner’s observations), it is interesting to think how long this look persisted with goth in its original era of the 1980s. We know that Kit-Kat lasted until 1989 and supported a crowd into goth-tinged music and adventurous dressing, but by 1987 we are reaching an era of peak mainstream goth with bands like The Cult, The Mission and Fields of the Nephilim grabbing TV appearances, festival headline slots and chart placings. There’s an iconic feature in the April 1987 issue of i-D titled ‘Six Cults for 87’ which includes “goth chics”. We see a septet of scenesters who share an approximate look of sleazy rock’n’roll mixed with hippie and a tinge of fetish. However, the text makes a point of stating that the “androgenous sexual flaunting of the early 1980s” has been abandoned. We also see a reference to the Kit-Kat going strong, and small print of what each model is wearing reveals a couple of references to Khaniverous.

It is, in effect, a last roll of the dice for the goth scene in the 1980s… a convergence towards a tired rockstar look which was embodied by The Cult as they became a heavy metal band of mullets, motorbikes and muscles. But, as we know, new variants of goth (and haute-goth) would rise from their slumber in the mid-1990s.

In part 4 I will have a deeper look at the origins of the term goth within this 1980s miasma.

Great stuff. That thing about the gay subculture running parallel with punk chimes with me. In Nottingham we moved from the Sandpiper to Shades/Whispers/Asylum because their door policy allowed unusuals in and kept the boot boys out, and there we saw the (younger) goth thing emerging

The pic of Simon Hobart in i-d reminds me of Mad Max 2.