How the world ends

On 1980s goth subcultures (part 1)

I have written two long essays on goth. The first one goes back over my own experiences of the scene as it was formed and named in the early 1980s. As usual, it is driven by a series of looks and subcultural facets. As usual, I try to dredge up memories, excavate supporting evidence, and add some (reflective) context. The second article looks at the persistence of goth through the lens of ‘haute goth’ fashion. Again, this is semi-autobiographical, as it documents my own (seemingly natural) inclination towards t h e s e b l o o d y d e s i g n e r s. Like I can’t help myself (even though the last thing I’d consider myself is some sort of goth malingerer hanging around Whitby or whatever). The articles are relatively intermeshed, so I’m tempted to run them one after the other, to merge the old with the new. In addition, I’m going to have to chop them up, so it will start reading like a science book with sections 1.3 and 2.2 etc.

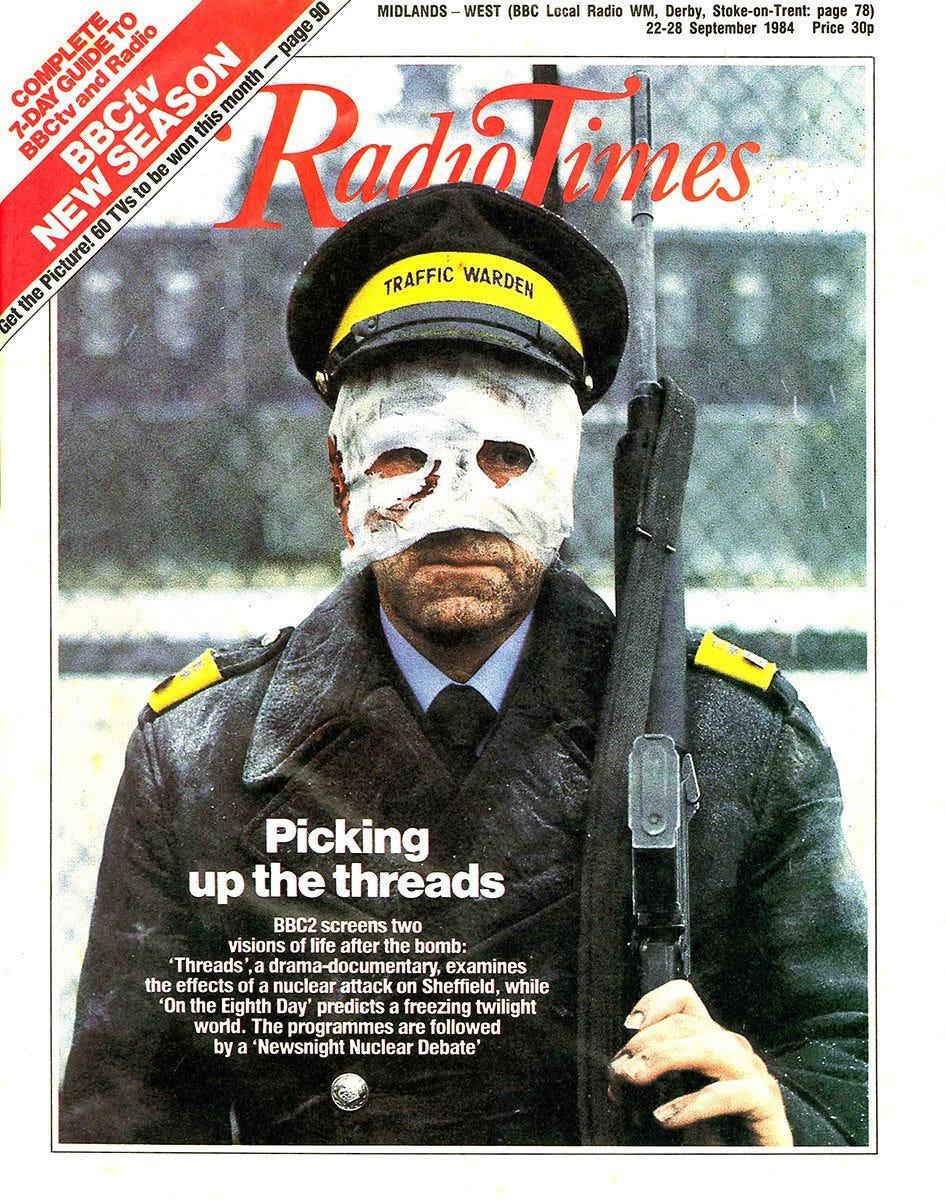

As the 1980s unfolded, gothic facets, sensibilities and aesthetics developed as a material, affective and tactile backbeat to our subcultural lives, coming in to a critical mass around early autumn 1983 to be expressed in music and fashion. Populist punk at the end of the 1970s during The Winter of Discontent was remarkably upbeat and silly, and this clearly couldn’t last. It was supplanted by a general aura of pessimism and hopelessness-of-critique, with dark motifs of horror and apocalypse in band names, song titles and lyrics, and an accompanying look that marked out a kind of readiness for the end of the world. It certainly didn’t entail (at that point in time) a sudden yearning for the (classic) gothic of Byron, Shelley or TS Eliot as subcultural bedfellows.

This wider use of the term gothic (or even the capitalised Gothic), as a descriptive attribute applied to music, pre-existed this early-1980s pessimistic turn. That’s an important point. The darkness and dankness of early 1980s paranoia-fed subcultures quickly congealed into something more manifestly cohesive and tactilely bounded, to eventually acquire a name: goth. This then, unexpectedly, became a subcultural juggernaut with both longevity and a tendency to retrospectively go back and claim a coherent and culturally polyvalent heritage. It is persistent and slippery, with no less than three lengthy tomes written in 2023 to try and explain the phenomenon of goth (for the record, John Robb’s is just too vast and unfocussed claiming anything and everything can be goth, Lol Tolhurst’s is just a poor rock’n’roll memoir, whilst Cathi Unsworth’s is much more interesting and rewarding and has a lot of resonance with my own approach and understanding).

Goth as both a music-enthused subculture and an endearing fashion impetus is a complex topic, hence the overlapping essay examining the ‘haute-goth’ strand of avant-garde fashion. For now, this first essay concerns my own encounters with the early-1980s pessimistic turn and what I see as the origins of ‘my’ goth in observing the music, gigs and fashions of the time. This was particularly so in the north and even more so around Leeds with events like the Futurama festivals held in the vast and unforgiving Queens Hall from 1979 onwards. It was more of an everyday and workaday gothic-becoming-goth, a subcultural scenographic and cross-modulating background drone of angst and despair: black clothes, black hair, either lank and limp or backcombed and sprayed.

Finding a common cause in nothing good coming, preparing for the end-event. Nuclear war, industrial meltdown, brutal strikes, IRA bombs in seaside hotels. In many regards it melded with the concurrent anarcho-punk image of black and weatherworn clothing, or the UK82 look of leather jackets, band tee-shirts and tight black trousers, or the shock-horror-rockabilly look of The Cramps, or the growing culture of following bands as explained in the previous essays on Theatre of Hate. A disparaging and typically snooty review of Theatre of Hate’s May 1981 gig in NME indicated this line of approach into goth with journalist Andy Gill reviewing the audience as much as the band: “minor heroes of the bleak, post-punk Gothic goons along with Killing Joke, Bauhaus and all those other names etched in white paint on black Lewis leathers”. Gill had already proffered a bunch of derogatory terms aimed at the scene in his autumn 1980 review of the first Bauhaus LP, conjuring up “modern monochrome” and “Gothick-Romantick” (the wordplay being “thick”) for the post-Ants fan cultures. Gothic already, but not quite goth, not yet named.

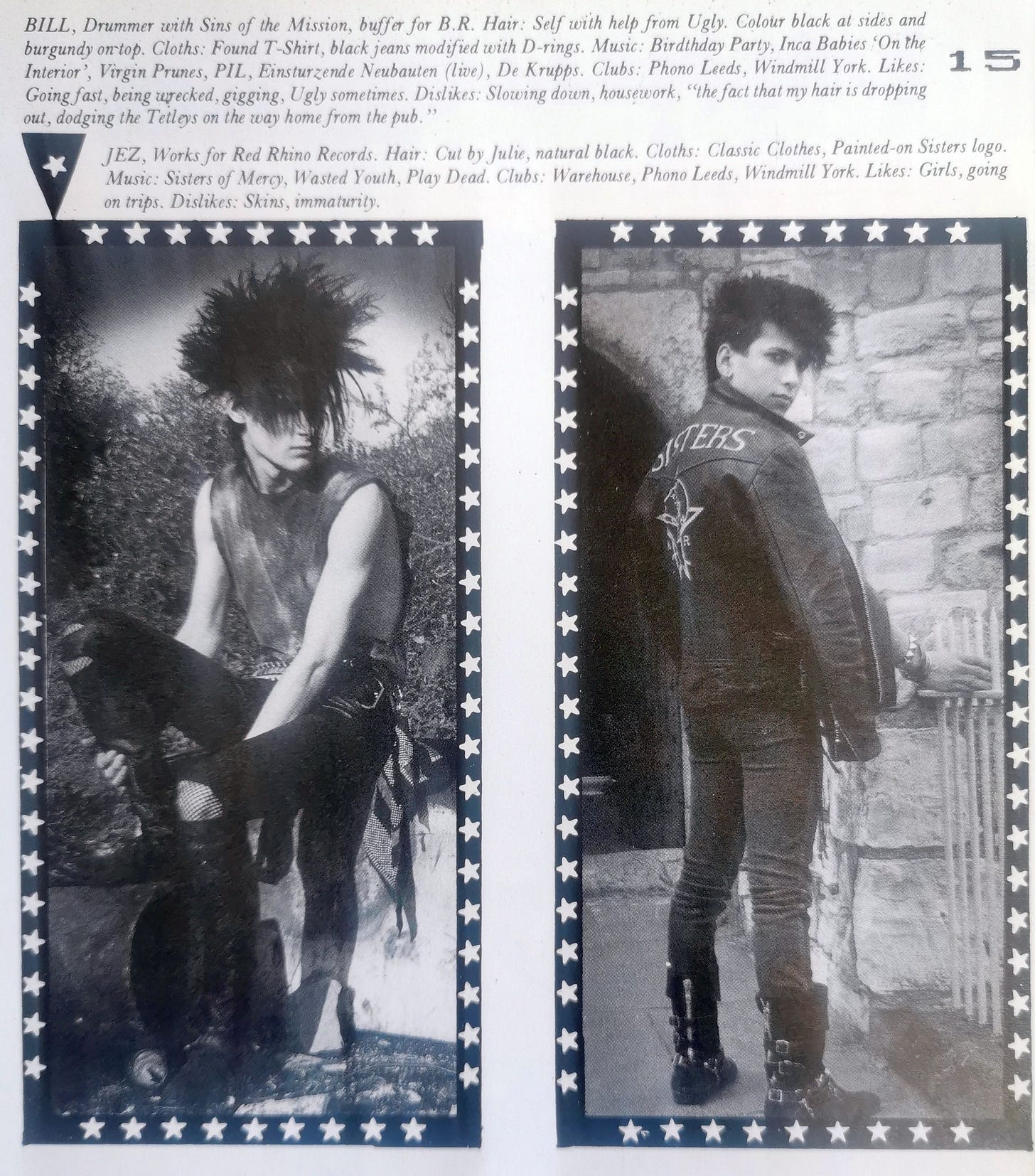

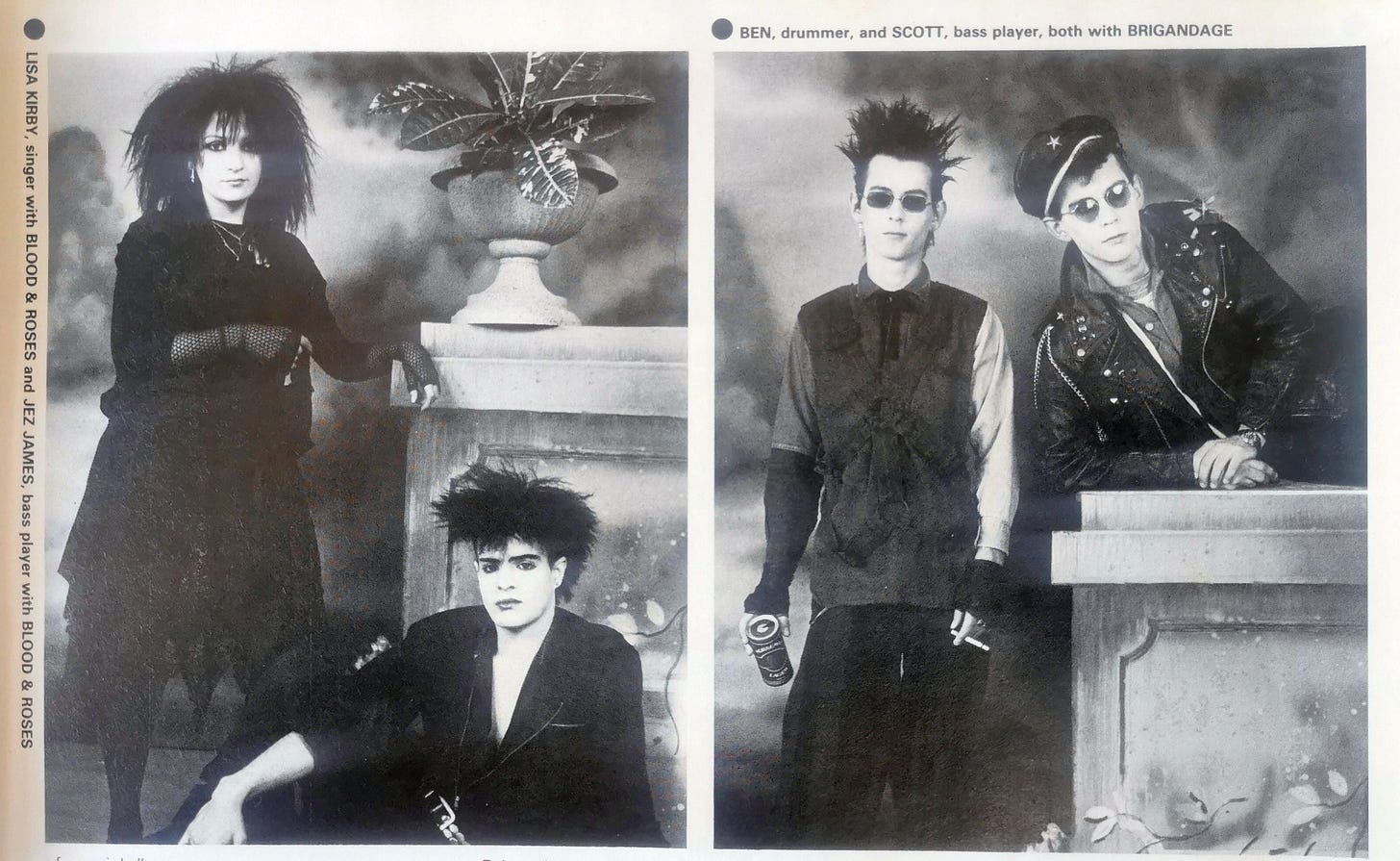

Fast forward a couple of years. The Leeds/York photo-feature in i-D issue 14 (autumn 1983) captures the maturing and dovetailing-of-scenes look perfectly, complete with graveyard and church backgrounds, even though the truncated g-word is not yet in use. An attempt to coalesce a music, look and scene briefly flickered in early 1983 with the ‘positive punk’ genre, a claiming originally in NME by journalist Richard North based around a handful of London-based bands such as Brigandage, Blood and Roses and Ritual. A more visual and style-oriented version of the same article appeared across multiple pages of The Face in April 1983. Even though this almost pre-packaged new scene was not labelled as goth, it is possibly the closest homogenised precursor as to what would follow later in 1983. Positive punk is one strand of the disputed timeline of the goth subculture – in terms of both coming-to-be and naming – that catches out many historians, and I revisit it in detail in the longer essay on haute-goth fashions.

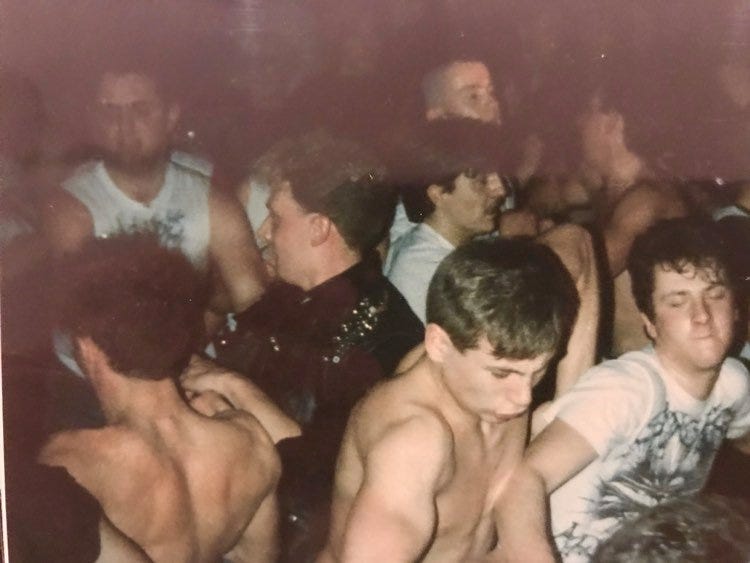

It was an odd time. Everything was transitional, amorphous, and ephemeral with no hard and fast demarcations. There was a long period when it was this hybrid or catch-all look – mutating punk meeting fleeing new romantic – tee shirts with radically cut off sleeves pulled down the rib cage, paired-up studded belts and wristbands, beaten up black drainpipe jeans. ‘Alternative’ club nights or DJ sets before and after gigs at places like Retford Porterhouse and Leeds Warehouse, a 1983 blend of early hip-hop, electro, Divine, Grace Jones, ‘Blue Monday’, Devo’s ‘Whip It’. These more post-punk-dance tracks were mixed with guttural and ‘gutter-al’ classics like The Cramps’ ‘Human Fly’ and Virgin Prunes’ ‘Baby Turns Blue’ where you could pose and preen, walk up and down and gesticulate awkwardly. The tempo would be raised with a bit of classic Theatre of Hate and Killing Joke’s ‘Eighties’, before the rowdy ‘chicken dance’ standards like The Birthday Party’s ‘Sonny’s Burning’ or Southern Death Cult’s ‘Fatman’ with their churning riffs resembling a tumultuous ocean prompted an explosion of limbs.

For a few brief moments during these proto-goth chicken dance numbers the dancefloor resembled Turner’s 1840 painting The Slave Ship, a harrowing and explosive depiction of the horrific throwing overboard of slaves as part of a financially-motivated insurance action. As well as the subject matter being distressing, Turner also creates a visual discomfort, deliberately removing the horizon and applying a messy multitude of convergence points. The dancefloor, or the front section of gigs, took on this frenetic appearance, with hands being shot up in air at orchestrated moments – eerily resembling the perishing slaves in the roiling and unforgiving sea: “Hands up, who wants to die?”.

This origin of goth as a straightforward subculture following on from punk, part of a wider panoply of scenes partly inspired by the despondent nature of the times but also partly enabled by a desire to dress up, shock and belong, is a history that is now obscured or even buried. Goth often claims a tabula rasa of subcultural lineage, offering in response a link back to an exogenous strand of pre-subcultural literature, architecture and aesthetics. My position is that this is not a necessarily accurate picture – in the 1980s post-punks wandered in to the goth subculture as a regular subcultural look on offer with a plethora of exciting new bands developing a distinctive sound – descending melodies, foregrounded bass, distorted guitar, tribal drums or crisp drum-machines, swirling keyboards, melancholic aura. There was a common motif, a trigger-switch between the lugubrious verse and a scathingly delivered chorus of fizzing nihilism, adumbrated by the bone-snapping crack of a drum machine. In 1983 and 1984, bands like Sisters of Mercy (‘Alice’), Play Dead (‘The Tenant’), Sex Gang Children (‘Sebastiane’) and The March Violets (‘Walk into the Sun’) were the masters of this sound – a new music that engendered a sequence of moping and mooching following by a burst of manic arm-waving. A dance that was seemingly made in Leeds. It was the equivalent of the successful stop-start ‘handbrake punk’ utilised by UK82 bands like Anti Pasti.

In the second part of this article I’m going to look at the now-hallowed goth bands that are said to have created this scene, such as The Cure. To unpack them and maybe even un-goth them.