In the first part of this article I outlined an inherent ‘declinism’, at times apocalyptic, in the post-punk environment of the early 1980s. This did not solely convert itself into goth, or nor did goth solely consist of aesthetic elements and stray wanderers from this bleak scene. But it played a significant part. There are other avenues to explore, such as the post new romantic clubbing culture that fed into goth, and I will cover this in the subsequent article. There is also a case to be put forward that goth was actually a subcultural tabula rasa. In a nuanced sense this is true – every newcomer to subcultural journey starts somewhere. And so, subjectively, this is a phenomenological tabula rasa to the newcomer. Goth, as it took shape, quickly adopted a powerful aura such that it felt like a new beginning at the objective level. And so those alighting on their subcultural journey with goth felt an immediate strong bond. This bond asserted differences and a break with the past. And so newcomers who swelled the goth ranks had a particular (negative) attitude to punk, and also started to insert different bands into a backdated goth lineage…

However, let us reiterate. Without dispute there were plentiful strands of cavernous and gloomy music within the wider punk and post-punk slew prior to 1983, and the lyrical themes and mode of delivery (the grain of the voice) often relied upon a mournful aura or matter-of-fact macabre. We are thinking of Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Damned, The Cure, very much Joy Division, and that at-the-time-unclassifiable first Bauhaus single of 1979. The one that eventually became a goth anthem and holy grail. The first four of these bands are now suggested as being the unifying force behind goth, and I had seen all of them at least once in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But it certainly wasn’t some kind of goth(ic) masterplan as we are now led to believe. More a case of disparate elements with disjointed fans, diverse influences (the glam or no glam dilemma) and certainly no unifying term of ‘goth’ or distinctive homogeneous subcultural look. Not yet.

The Cure, for example, were very much something different as the 1970s lurched into the 1980s. They are now claimed as an undisputed goth band, and the artists themselves will claim that they were always gothic in attribute and sensibility, but it is all a bit blurred. Michael Bracewell’s always-scintillating reflections on punk and post-punk music in his 1997 book England is Mine fix on The Cure, and he sees them as something specific to an expression of suburbia. The late Mark Fisher in his K-Punk blog, builds on Bracewell’s theory, and looks at what he labels as the “unholy trinity” or “essential triptych” of the albums Seventeen Seconds, Faith and Pornography. These releases in 1980, 1981 and 1982 follow the band’s more obdurate off-punk debut Three Imaginary Boys, offering what Fisher describes as a barely-progressing journey of “faltering self-discovery and existential experimentalism”. It’s not gothic (or goth, even if the term’s not quite invented at the time) but more so a low-lying unshakable moodiness, archly described as a “post-punk psychodrama” by Bracewell.

The Cure made an existentialist entrance of sorts with the single ‘Killing an Arab’, launched in the final week of 1978, and based upon Albert Camus’ novel The Stranger. A literary intent for sure, but the single exuded a catchy stop-start jerky post-punk aura with a sonic equivalent of the tipping moment in the novel when the main character shoots the Arab with a “crisp, whip-crack sound”. This arrangement helped propel its popularity. The trio of albums examined by Bracewell and Fisher continued in the existentialist literary vein but forsook any appeal to popularity, unwrapping layers of questioning authenticity like a sixth former’s take on nineteenth century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. It certainly wasn’t theatrical self-pity, tales of spurned love or prescriptive end-of-the-world scenarios such as would become goth staple elements.

Furthermore, at the time, the band had a disaffected and disinterested look that matched this angsty introspection: awkward school jumpers, raincoats, plimsolls, and that stance shared by bands like Simple Minds which involves wearing a blazer but pushing your hands deep into the pockets. If we now think of the first throes of the goth subculture as having a sartorial imprint, then The Cure were a long way off from that. Instead, they personified being uncomfortable in your clothes: not fitting for the not fitting in. However, by 1983 something musically (lyrics, mood, instrumentation, production techniques) asserted itself as shared outlook (gathering in The Cure, Siouxsie, The Damned and Joy Division), and the name goth was bestowed. As we move forwards from that point in time we also move backwards, and all these aforementioned bands are suddenly goth and contribute to the goth look (even if that is not necessarily the case). We can add here that The Cure’s look evolved: Simon Gallup had the Johnsons rock’n’roll suicide look for Pornography tour of 1982 though Robert Smith was still in his raincoat. The full gothic clown look of Smith was cleverly constructed for Tim Pope’s video for ‘Love Cats’ in October 1983, at the time when goth was first named as a ‘thing’.

If goth was strong enough to create a fixed home for the subcultural waifs and strays of the early to mid-1980s, then the fostering of exogenous literary and cultural links was a further bonus. It impacted the same way as literary themes were grafted onto the post-punk scene – authors such as JG Ballard and William Burroughs. The listener to the genre was led into the literary sphere, a process of inculcation by the bands and label managers. It was seldom the reverse case with the reader being led into (or feeling a natural inclination towards) the subcultural music scene.

Additionally, it is important to note that first instances of the named goth scene proper did not flaunt a literary connection (gothic, existential or otherwise), but this came later as the scene quickly developed a stronger sense of identity. This latent literary attachment to goth is sometimes used as a bridgehead back to a pre-goth moment, when the literary term gothic is used by Tony Wilson (in a description of Joy Division) and a review of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ 1978 album The Scream. Goth historians conflate these instances to propose that goth started as a nameable thing in the late 1970s exhaust fumes of punk – I feel that this is more than a little disingenuous. It was a look taken on by certain musicians, and adopted by certain fans, but it was disparate, muddy and certainly unnamed. In fact, later interviews with Banshees bassist Steve Severin has the band distancing themselves from the goth scene as it is formed and named in late 1983. They feel that their own melding of more cerebral romantic and gothic literary influences has been all but eradicated for a simple celebration of deathly surface appearance in the first proper wave of goth subculturalists. This rebuking of the term goth by Severin is strong empirical evidence against the supposed literary aspects of the cohort of goths at the inauguration of the named subculture.

I will return to Tony Wilson, Joy Division, disputed literary attachments, and the moment(s) of NAMING goth in my essay on haute-goth fashion, but for now I offer my account of how that “cross-modulating background drone of angst and despair” started to coalesce in the early 1980s. In June 1983 British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher would win her second term, and life for young people who had been hiding in arts-funded crevices of subsidised venues and events would now be drawn into the open to come under attack. Counter-cultural responses were varied, but with their typical humour Crass released their excoriating single ‘Who Dunnit?’ which asked the question we seem to be asking again and again: “Birds put the turd custard, but who put the shit in number 10?”. Thatcher was galvanised by her success; obviously the miners would be her key battle, avenging the defeat that the miners had handed the Conservative government in 1972 at the Battle of Saltley Gate. By the end of the decade she would be confidently applying the same brutal police tactics from the miners’ strike onto the illicitly organised rave and free party scene.

In the background of the early 1980s and Thatcher’s tenure, nuclear arms and the possibility of mass destruction rose to the fore as a tangible reality. Photo series such as Brian Griffin’s London at Night (1983) and Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel When the Wind Blows (1982) brought home the real possibility of nuclear annihilation in the UK. This was topped off by the terrifying BBC film Threads, broadcast into living rooms on a Sunday night in autumn 1984. It was set in Sheffield and I was moving to Sheffield (from Derby) a week after I sat watching the programme, gripped in terror. People of my age who also watched the programme can still recall a multitude of specific harrowing and graphic scenes. I wrote in my diary just two words: “evil stuff”. Gothic times indeed.

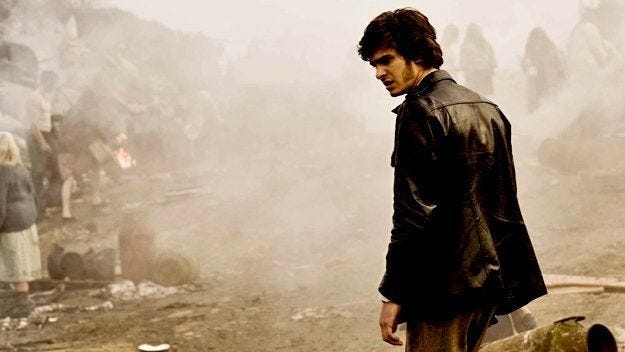

Wakefield-based novelist David Peace concluded his Red Riding quartet with the 1983 re-election of Thatcher. Though the arc of his four books covers the terror reign of the Yorkshire Ripper, the penultimate and final books seeped into a punk, post-punk and goth sense of murk and oppression with references to bands like UK Decay. As Thatcher struts in the confidence of her second term victory, youth subcultures retreat into the darkened corners of damp and decaying music and club venues where the impending destruction of the world is just a normalised muttering.

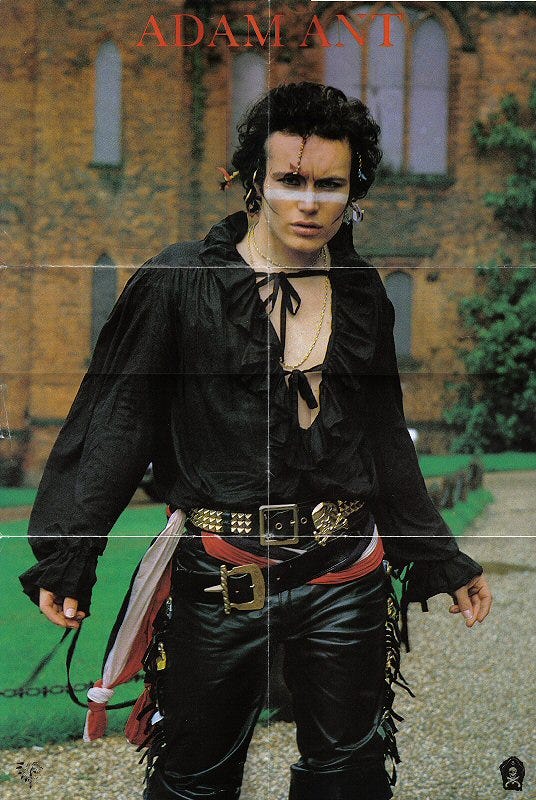

The early 1980s northern goth was not solely the theatrical goth that we now associate with the genre; hours spent inside crimping, backcombing and spraying hair. It informed many of the bands of the time, and the tribal following of bands tradition that I discuss in the earlier essay about hitch-hiking and subcultures. Bands like Southern Death Cult who flourished in 1982 are now labelled as an early goth band, but I’d disagree. Their own (incredible) look, and the looks adopted by their hardcore fans, channelled a multitude of sources including anarcho-punk gloom, UK82 punk apocalypse, Adam and the Ants exhibitionism, Theatre of Hate utilitarian road-readiness, and possibly a twinkle of early (but as yet unnamed) goth.

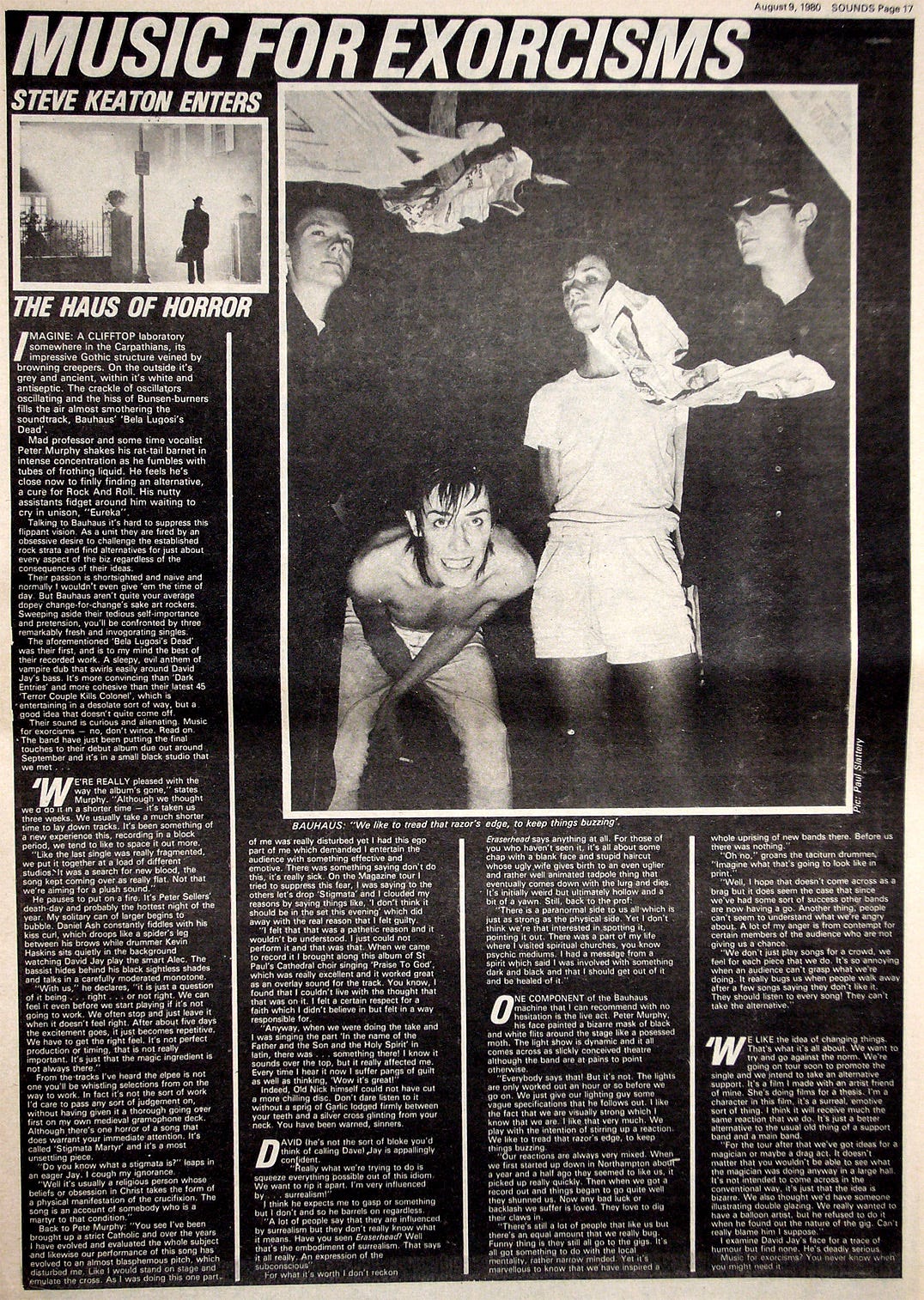

Probably my first goth moment (aside from seeing Bauhaus and Killing Joke in 1980) was witnessing UK Decay in December 1981 at Derby, playing the Rainbow Cinema, a fleeting venue that had been hurriedly utilised following the demise of the Ajanta Theatre at the end of 1980. UK Decay, along with Bauhaus, were one of the more fully formed goth bands in terms of sound, song themes and imagery (though Bauhaus started out sounding goth but certainly didn’t immediately conform to how we think goth bands look). However, and I need to be incredibly clear here again, the term goth as a distinct genre or fan culture was not in existence, instead bands and journalists would make oblique references to a gothic influence or attribute. UK Decay can claim some kind of first here, with Steve Keaton’s February 1981 Sounds feature catching them on a European tour amidst gothic architecture and literature, and employing the title “the Face of Punk Gothique”. The concept and term did not quite bed (UK Decay were never a band feted by the music press). In fact, as late as August 1982, UK Decay were being described (by Record Mirror) as part of a scene of “semi-theatrical nihilistic acts”. So, definitely not goth.

Bauhaus meanwhile simply confounded the music press. They were part of a handful of bands who were deemed to have artistic pretensions way above their meagre punk rock’n’roll stations. The journalist intellectual snobbery of newspapers like NME despised such bands and took time to ridicule them by turning their artistic fumblings against them in a public schoolboy type one-upmanship of outsmarting them with art-words. I already referenced Andy Gill’s slew of insults towards the band in autumn 1980. However, to his credit, Steve Keaton in Sounds was sensing something here, just as he would with UK Decay a few months later. He gave Bauhaus a feature in August 1980 under the title ‘Music for exorcisms’, and so we have a gothic fossil set in place (even if the band were trying to pass themselves off as a surrealist assault on religious strictures).

There was a subcultural langue and parole (the extent of the words we could use and the extent of the words we chose to use) and goth had not formulated as an accepted genre term even though gothic was an increasing but loosely applied descriptive term. Furthermore, both UK Decay and Southern Death Cult split up early in 1983, before the term had come to an accepted use as a subcultural grouping. UK Decay and their ilk cultivated and catered for a following, initiating rituals such as placing hitch-hike signs behind the stage and having dramatic crescendos of music where the audience removed their studded belts and swung them around in a frenzied dance (known as the ‘Dresden belt swing’ and named after one of their typically crescendo compositions). Studded belts were not functional belts, they were worn as hip-slung bandoliers over shirts and jackets at an angle.

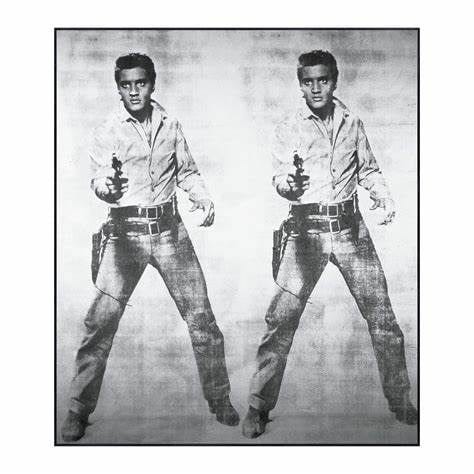

A fashion and art note diversion: The wearing of two thick belts is immortalised in Andy Warhol’s numerous prints of Elvis Presley as a be-quiffed gun-toting cowboy (for example the 1963 work Triple Elvis) in which a still from the 1960 film Flaming Star is endlessly reproduced. Elvis has a front-on legs-apart stance with the pistol drawn directly at the viewer, his belts arranged horizontally on top of each other such that the first holds up his trousers and the second supports his gun holster and knife sheath. The Elvis series marked Warhol’s move into screen-printing and reproduction as high art, deliberately disrupting the hierarchies of artistic techniques. An instant success, Warhol imbued infinite cultural cachet into this Elvis still, and in 1993 the artist Gavin Turk paid a bizarre tribute with his sculpture Pop which depicts the artist imagined as Sid Vicious performing ‘My Way’ in turn imagined as Warhol’s Elvis. Sid Vicious (and the first cohort of punks) didn’t seem to wear the double belt combination, though (in the words of writer Peter Stanfield) the ‘third generation rock’n’roller’ Mick Farren did around 1970.

Farren was very much a punk-before-punk, and the hip-slung double-belt accessory re-emerged after punk circa 1981 with both ‘Stand and Deliver’ era Adam Ant and the official second-wave (UK82) punks. These are evident in back page advertisements for companies such as Printout Promotions, who sold studded belts, bullet belts and something called the “bandellero” which can be worn on the hips or shoulders (and retailed at £8-50).

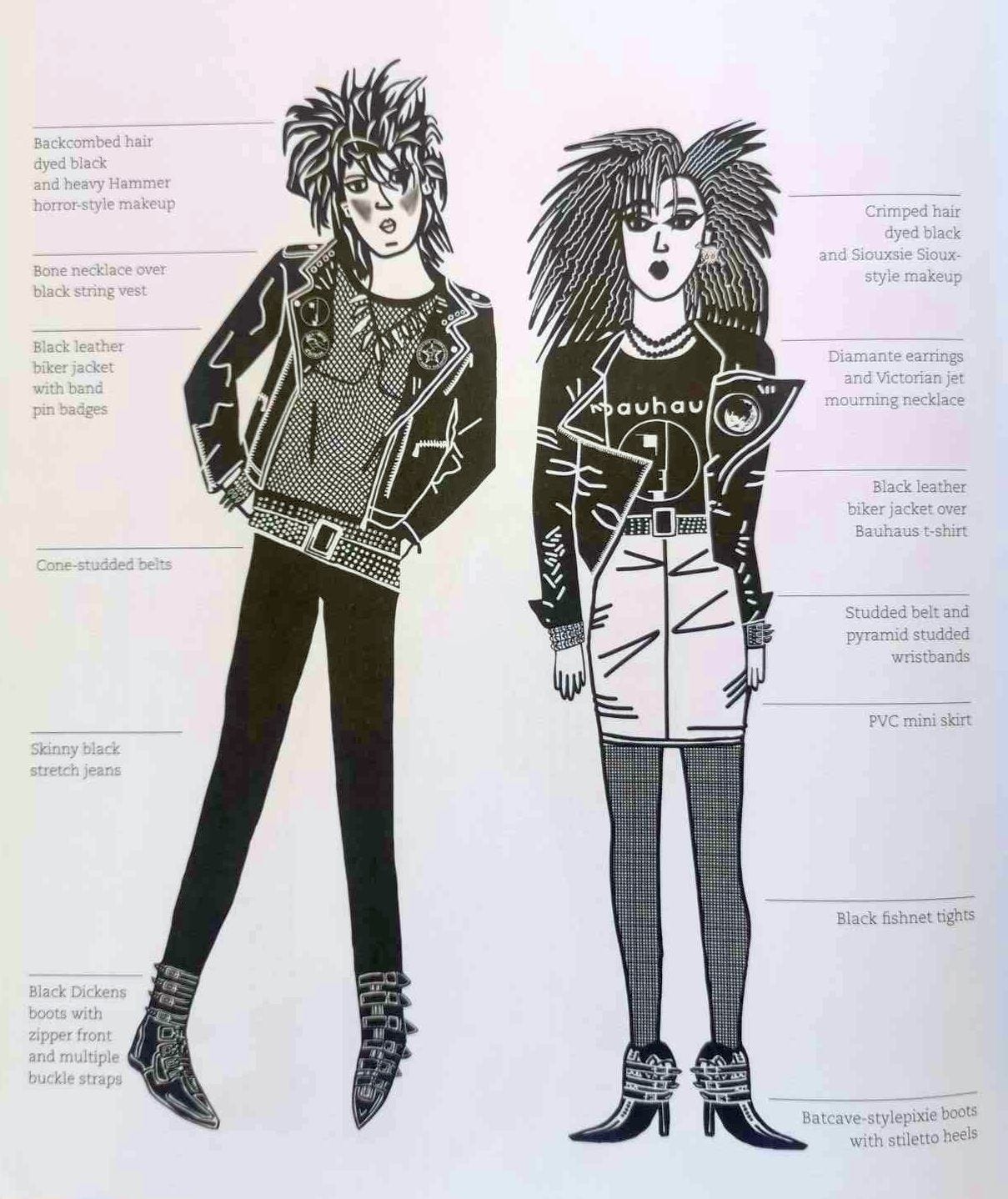

The astutely observant subcultural archetype drawings by Florence Bamburger in the back of Sam Knee’s The Bag I’m In identifies a double studded belt with this epiphenomenal punk movement and its segueing into goth. UK Decay (and Bauhaus) fans often sported two studded belts, arranged at a diagonal cross intersection like a Mexican bandit. If one happened to whack you round the head it bloody hurt. I left the gig predictably hypnotised by the spectacle and proto-goth gesamtkunstwerk, bought a cheap black canvas jacket, cut the arms off with some ragged edge pinking shears, added some rows of conical and pyramid studs, and painted a UK Decay logo (self-performing autotelic letters that gradually ‘decayed’ from left to right) on the back using the trusty Tippex. No pictures exist. What a shame.

The final part of this article concludes with my personal and somewhat underwhelming goth excursions of late 1983 and early 1984.