Itching, Scratching and Hobo-Couture

Westwood-McLaren’s ‘Nostalgia of Mud’, ‘Punkature’ and the ghost of Fagin

In a documentative sense, this post follows on from the earlier post exploring Westwood and McLaren’s re-strategising with their ‘Pirate’ and ‘Savage’ collections in 1981 and 1982. In a narrative sense, the writing mixes a more autobiographical style based upon actual garments purchased post-2000, even though the garments are generally considered in ways that they link back to 1980s subcultures and music scenes. This method will feature more often as the project moves forward. It might not be for everyone, but please give it a go.

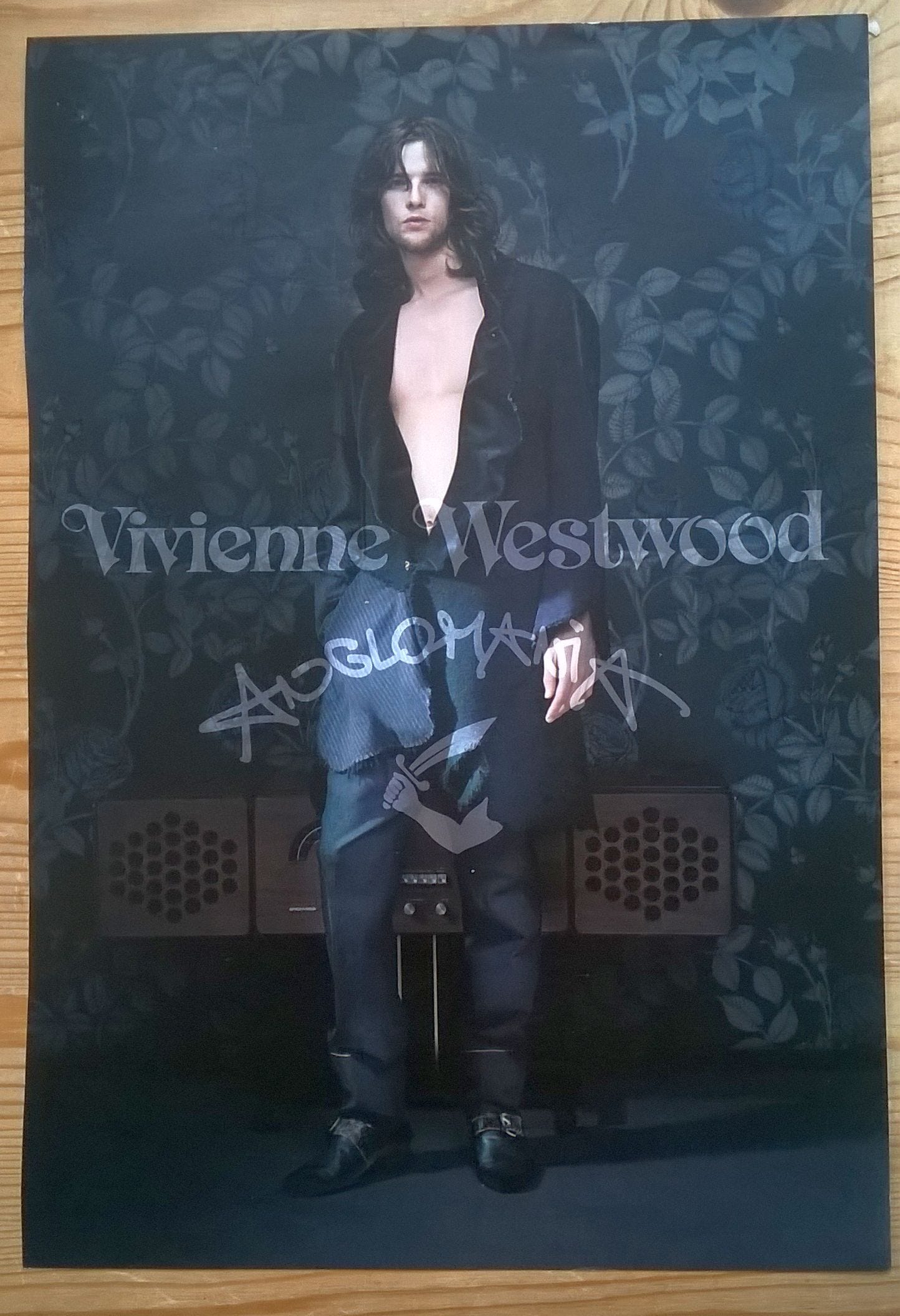

In winter 2003 I purchased a Vivienne Westwood Anglomania coat. It was one of those moments when I saw a garment in a shop and was just stopped in my tracks. It had cut, construction and material that eschewed all the norms of fashion and wearability. The coat is stitched together from rough fabric that looks to be recycled from cast off bits of upholstery and sacking. It gave me a strong but deictically oblique memory, from childhood, of spending an afternoon sitting in my Grandma’s yard and cutting apart old sofas and chairs and finding pre-decimal coins and mouldy peppermint sweets amidst all the hidden springs, stuffing, and splints. Tearing through the upholstering fabric bombarded you with the dust of ages, the smells of a trapped past condensed and released, the physical sight of the ruins of the disembowelled sofa taking up twice as much space as the intact object. Not the clearest rationale for purchasing a coat, but there you go.

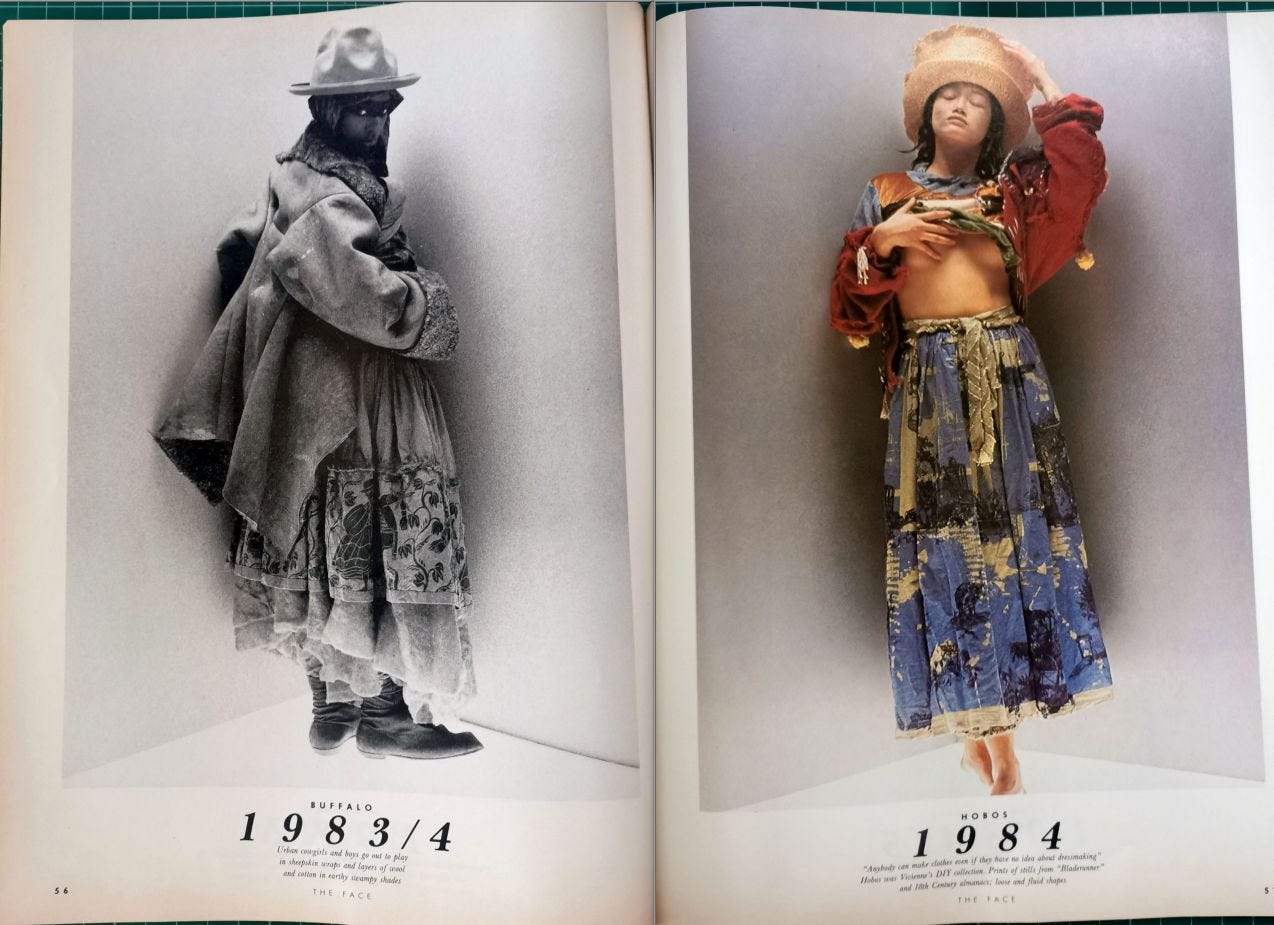

At the time I did not realise that it was a perfect reproduction of a heritage piece. The Westwood Anglomania clothing from the early 2000s consisted in part of reworking classic designs from the whole of the designer’s lineage, but things are not lifted wholesale. This coat originates from the time of the consecutive ‘Nostalgia of Mud’ (A/W 1982) and ‘Punkature’ (S/S 1983) collections for Worlds End, the first collections McLaren and Westwood took to show in Paris in 1982 after participating in the London Olympia shows twice in 1981 with ‘Pirate’ and ‘Savage’. Another step away from street and towards something new, with the partnership still finding an incredibly productive synthesis. ‘Nostalgia of Mud’ is where the iconic ‘Buffalo’ look was launched, with various distinctive and innovative touches and details such as underwear worn on top of outwear. There is no radical phase change into the subsequent ‘Punkature’ collection, the movement between the two a more blended evolution that Westwood occasionally employed before undertaking a more radical shift.

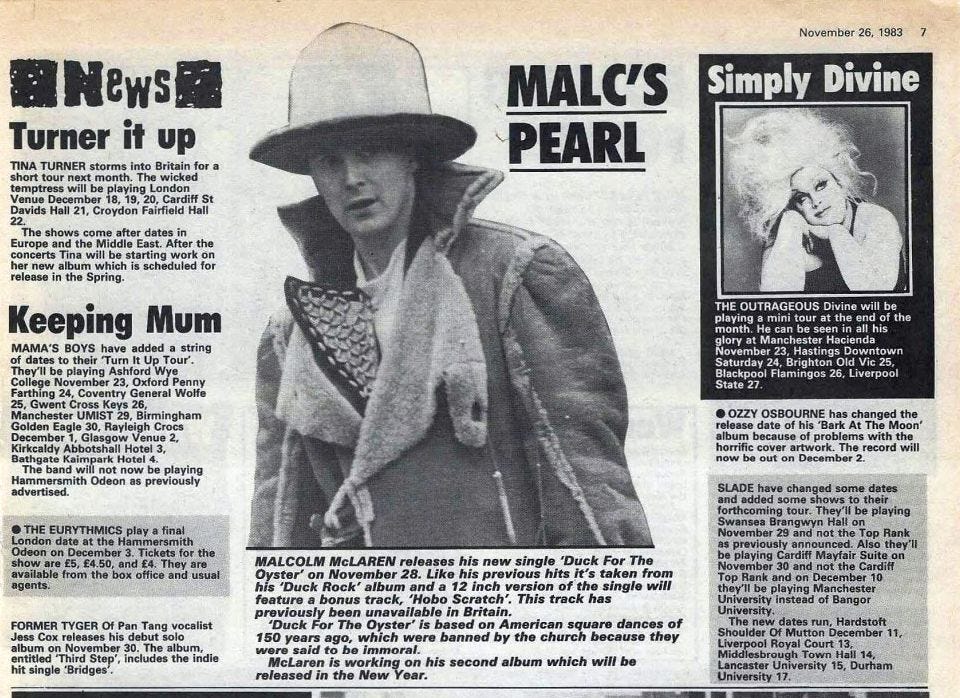

‘Nostalgia of Mud’ jumped away from the previous collections to establish a bold new look scavenged from the far corners of culture and history, whilst ‘Punkature’, often dubbed ‘Hobo’, added a trampish (anti) aesthetic on top of this. Both collections were ground-breaking and as per usual used by McLaren to launch his ongoing music projects that birthed the ‘Buffalo Gals’ single (November 1982) and Duck Rock album (May 1983), his association with Bow Wow Wow now a distanced and retreating speck in the rear-view mirror. To give McLaren his due here, this project was a key launch pad for the UK embracing hip-hop culture.

As with ‘Pirate’ and ‘Savage’, the distinctive clothing from these two collections was all the rage in the early 1980s, dominating the pages of i-D with vox-pop insights into the emerging club scene showing many people luxuriating in these ragged and mis-proportioned garments. To someone like myself, living in the provinces, they were hallowed and unattainable, otherworldly clothing. The squiggle print garments of the ‘Pirate’ collection had infiltrated many towns and cities, but prices were feverish – this new clothing was in another atmosphere entirely.

The deliberate ragged and degraded effect is more clearly evidenced around the second collection ‘Punkature’, even though it is signalled with ‘Nostalgia of Mud’. The strange name derives from the French term nostalgie de la boue, which commonly translates to nostalgia for mud. The term relates to a predilection to low-life culture and degradation, reactivated by the acidic observer Tom Wolfe in his 1972 book Radical Chic that honed in on academic left-wing stereotypes channelling peasant aesthetics in the late 1960s. You see it in the present era, with striking lecturers dressing up in in jeans, DMs and work jackets on the picket lines akin to 1980s striking miners. Whilst McLaren had been at the heart of left-wing activism with his student occupations at various art schools in the heady period around 1968, the taking of a critical or ironic stance such as that adopted by the mischievous Wolfe would have proved appealing. To take this to an aesthetic or vestimentary level, even better. And, of course, McLaren (like his beloved situationists) always dressed up. Or maybe it’s McLaren’s rock’n’roll revival side coming through, with the plodding pop of ‘Tiger Feet’ and ‘the Cat Crept In’…

As Paul Gorman documents in his research on McLaren, Wolfe’s work was one of a number of books that directly influenced the themes and rationale for Westwood and McLaren’s clothing. Its individual influence was perhaps even greater, as the pair also opened a separate shop on St Christopher’s Place off Oxford Street in March 1982, excavating the floor leaving heaps of mud in an attempt to imitate an in-situ archaeological dig. This is about as far as you can go with an anti-commercial and anti-functional strategy – most likely too far. My proposal in the earlier post that their rebellious creative fire was catalysed by constantly renewing and reshaping the three elements of fashion, pop music and physical space also bears fruit: McLaren was initially anxious to tear up the expensively refurbished Worlds End, but Westwood sensibly dug her heels in. As a compromise, this new ancillary experimental space is opened up. Here McLaren is pushing boundaries to do everything to subvert the process of shopping and consuming. This shift from mud as metaphor to mud as metonym reflects the pair’s literal translation; from nostalgia ‘for mud’ to nostalgia ‘of mud’, a convenient miscarrying. The shop, as well the McLaren-Westwood partnership, would not see out 1983 – it had volatility coursing through it at every juncture.

Other important designers who are labelled as sharing a punk and post-punk ethos such as Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto were garnering interest in Paris, and portraying the motif of ragged and destroyed fabrics and precarious garment construction – boro boro – quickly became a popular method. In 1982 and 1983 Yohji Yamamoto presented distressed and ripped clothes, described as faux vieux (already worn), though Yamamoto openly admits (in the 2011 V&A book documenting their exhibition on his work) that he had previously visited to seek out the early incarnation of Worlds End. Rei Kawakubo, founder of Comme des Garcons, had taken on the Paris world a year before Westwood and McLaren, and there are (typically) contradicting reports on who influenced who in terms of creating clothing in this hobo mode. Kawakubo is generally noted as coming in to public view through her A/W 1982 collection entitled ‘Holes’ which mirrors Westwood and McLaren’s ‘Nostalgia of Mud’ in terms of the aforementioned boro boro aesthetic, and Westwood’s autobiography suggests that the opening of the new shop on St Christopher’s Place – effectively putting their work on retail display before the show - led to Kawakubo taking up the tattered look for her own collection. Kawakubo’s subsequent S/S 1983 collection, shown in October 1982, garnered her the ‘apocalypse clothing’ tag from bemused fashion critics.

However, there is a further twist in the tale here and a slightly deeper crossover. Early coverage of the Comme des Garcons collections are not prolific, but the A/W 1981 collection is generally accepted as Kawakubo’s opening engagement with Paris (and the wider fashion world) even though this show and the subsequent S/S 1982 show were deliberately low-key and outside of the main arena. Incredibly, this first recorded collection is entitled ‘Pirates’ and the sparse evidence of photographs indicate a similar aesthetic and historical reference points to Westwood and McLaren’s ‘Pirate’ collection of the same season. So, both the pirate theme and the holes theme inform subsequent collections for both designers at the same instance. The key difference is that Kawakubo is almost duty-bound to work in total black, whereas Westwood and McLaren move in the opposite direction into pure hyperreal colour for ‘Pirate’ and earthen shades for ‘Nostalgia of Mud’. It is also evident that Westwood and McLaren’s ‘Pirate’ is rooted in British street fashion, while Kawakubo’s work is rooted in more formal couture – but they both meet in the middle with a shared aesthetic and approach to cutting and tailoring.

The first coincidence of ‘Pirate’ and ‘Pirates’ begs the question of how this came about: an incredible zeitgeist-derived synergy or happenstance, some loaded reciprocity where one party is influenced by the other, or a possible pre-planned symbiosis where they work together. The lack of referencing between both parties in recent historical works suggests that there was no collaboration or shared field of thinking, leaving the option that one party influenced the other. Of course, they could BOTH be influenced by Helen Robinson’s buccaneer-inspired designs for PX, but we’d better not go there.

Paul Gorman’s biography of McLaren makes a single, but important, reference to Rei Kawakubo. It is suggested that when the Sex Pistols perform their high-profile pair of gigs at the Paris Chalet du Lac in September 1976, there is an organisational undercurrent of Parisian fashion and art movers leading to the attendance of numerous fashion designers at the gig – Jean Paul-Gaultier, Yves Saint Laurent, Karl Lagerfeld and (perhaps most importantly) Kenzo Takada. McLaren uses the opportunity to dress the band up to a tee in Seditionaries clothing, making one of his typical subcultural gestures that merges music, fashion and attitude. As Gorman himself evaluates, the inclusion of Takada in the audience cements a bond between the King’s Road design partnership and avant-garde Japanese couture. This was 1976, and Takada had links to both Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, but how might this manifest itself in early 1980 as Westwood and McLaren curate and launch their pirate-themed range? A potential key link is the earlier observation that the Joseph boutique in Sloane Square was the initial stockist of the new ‘Pirate’ clothing in winter 1980 whilst 430 King’s Road was being revamped. The owner of the store, Joseph Ettedgui, had a contiguous path with Westwood and McLaren, with the opening of Salon 33 on King’s Road moving in to fashion retail in 1972 – the time of Let It Rock starting out further down the road. Ettedgui’s move into fashion was through him attending (as an enthusiast) Parisian fashion shows, meeting Kenzo Takada, and agreeing to stock his minimalist clothing – causing an instant sensation on the King’s Road fashion scene. With Ettedgui initially acting as the sole conduit of the first trickle of pirate clothing, and Takada being a convert to Westwood and McLaren’s designs, it is no large jump of guesswork to imagine Takada getting instantaneous access to the pirate clothing and sharing this with Kawakubo. An even cleaner solution to this riddle has Kawakubo as a regular visitor to 430 King’s Road from its very inception as Let It Rock.

Returning to the creative nexus of early 1982 and the birth of ‘Nostalgia of Mud’, a key design was the shearling ‘Buffalo’ coat, cut with rectilinear sections and assembled so that the seams are reversed and prominently raw, and worn such that the coat ties with crude fasteners made from the same fabric as the body of the garment. This is generally understood as an exemplar or imprimatur of the Westwood heritage, and is reintroduced from time to time but always retails at an extortionate price. It appears that this coat has now acquired the alternate name Fagin, but my reading of the name Fagin relates to the antagonist of Charles Dickens’ 1838 novel Oliver Twist. The Fagin coat is the garment I purchased back in 2003, the subject of this post.

Let’s do a bit of historical digging. Common to other Dickens characters, Fagin is motivated by both acquiring and hoarding fence-able commodities, also embodying a morally bereft avarice and miserliness (a miserliness that extends from being mean towards others and then to himself). In the canon of depictions of Fagin, his own appearance becomes a contradiction such that he is dressed in recycled and repurposed rags – much like the classic ‘Houseless and Hungry’ by Luke Fildes (an illustration for The Graphic in 1869). Fagin is a problematic character, and his depiction has shifted over time, though there is an anti-Semitic core to the character of Fagin in Dickens’ original story (and this is said to have been toned down for later editions of his work after his close friendship with a Jewish woman, Eliza Davies).

As Dickens’ work grew in popularity and proved to have longevity, Fagin is depicted across time in further illustrations and eventually film representations. The more obvious reading of the coat he wears – as an index of the character - is that it symbolises a stark opposite to ostentation, instead personifying an unwillingness to part with money on something as frivolous as clothing. Even this seemingly obvious explanation collapses under a more rigorous historical critique, with Henry Mayhew’s contemporaneous work of journalistic survey in the 1830s London Rookeries London Labour and the London Poor offering a more complex understanding of how and why people would dress in such ragged clothing. Mayhew pays particular attention to clothing and its relationship to the localised and striated poverty of the time, as well as documenting enterprises like the Old Clothes Exchange where discarded clothing was re-used by those in need. The prominent fashion academic Caroline Evans connects these degraded spaces of communalised clothing, via Baudelaire and Benjamin’s ‘rag picker’, through to practices of contemporary designers like Martin Margiela and artists such as Christian Boltanski and his installation for the exhibition Take Me I’m Yours, at the Serpentine Gallery, London, in 1995. In this case the exhibition consisted of piles of old clothing, and the participative aspect involved visitors filling a plastic bag and paying a nominal sum for the pleasure.

As Paul Gorman carefully recalls, the Sex Pistols manager and general raconteur had a strange synergetic relation with Fagin, seconded only to his admiration for flawed music mogul Larry Parnes. He recounts how McLaren’s fabulist grandmother had told McLaren as a child that Fagin was based on a real person, a Jew who was far too clever to have been caught by the authorities and that this person escaped to Australia and was responsible for the development of Sydney as a city. This set in place a seed of interest and admiration. McLaren developed into a contemporary re-imaginer of Dickens, intertwining his interventions into culture and politics through a Dickensian lens such as with Christmas stunts on Oxford Street. As manager of the Sex Pistols he designed the flyer for their finale UK gigs at Ivanhoes, Huddersfield, on Christmas Day 1977 based upon the original George Cruikshank illustrations for Oliver Twist.

However, the particular image of Fagin I include here (currently the reference image for Fagin on Wikipedia) is illustrated by the artist Kyd some 50 years after the novel, and amplifies the obvious anti-semitic characterisations. The isomorphism between the coat illustrated in Kyd’s stereotyping on steroids image and the Westwood design is undeniably very strong if not troubling, sharing the patchwork design of roughly hewn fabric in shape, composition and deliberate degrading. With the McLarenesque shock of red hair taking it way further than the Cruikshank images, it seems a puzzling and provocative choice as a reference point. Maybe its intricate detailing of the fictional garment is what counts here, an innocuous explanation.

Finally, the coat prompts for me a memory of punk times past. The advertisement campaign for Anglomania Winter 2003 focussed on this coat (in black) with the incredible image of a bare-chested model leaning against a black-tone regency wallpaper and straddling an incongruous heating unit. I should be too old to be drawn in to an Animal Nightlife type fashion chronotope, but it has me.

It is a decadent storming of the palace mood, stunningly beautiful and well-dressed revolutionaries flaunting the codes and conduct of proper attire, dressing down in the clobber of the privileged. Punk at a subcultural level was often (for many people) about dressing proper and well – looking to be assembled from rags and detritus but doing it with attention to detail. This chimes with Georg Simmel’s 1904 essay entitled Fashion, in that it encompassed both a socialising impulse (punk’s particular subcultural look as part of the scene) and a differentiating impulse (the effort of certain punks to create key amplifications, differences or hybridisations). There is so much more to it than a simplified homology espoused by the cultural academics (Winter of Discontent etc), there is also a sense of creativity and belonging. The haunts of late 1970s and early 1980s punk were often decrepit theatres and ballrooms such as London’s Lyceum, once palatial and resplendent in the architecture and décor of movements from neo-baroque to modernism, now falling apart at the seams. Interior fixtures such as balustrades and decorative ironmongery now decommissioned, defunct and coated in black paint. For me, the coat channels this long-past era and its reawakening by the punk scene.