Yesterday I visited the London Textile Museum to explore the Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London exhibition. It is something I’m interested in, though I’m always cautious about seeing this period of UK underground style creativity as being presented as something solely tethered to London (as the 2013 V&A 80s Fashion: From Club to Catwalk managed to do). A secondary reason for visiting was to help research a forthcoming project at Nottingham Bonington Gallery that focusses on that city’s role in 80s clothing, subcultures and clubcultures. I’ll talk about that in a later post.

As anticipated, Outlaws was very much in the London-centric mode, with brief mentions of ‘provincial’ creativity included when the people concerned decamped to London. So, there’s the obligatory mention of the Birmingham scene with Martin Degville and Kahn and Bell who went on to have stands at the Great Gear Market on King’s Road and the legendary Kensington Market. There’s also a brief mention of Nottingham graduates (David) Vaughan and (Bunty) Franks who found a bit of fame in London when they were picked up by the important shop Browns, and then went on the clothe a few popstars towards the end of the decade.

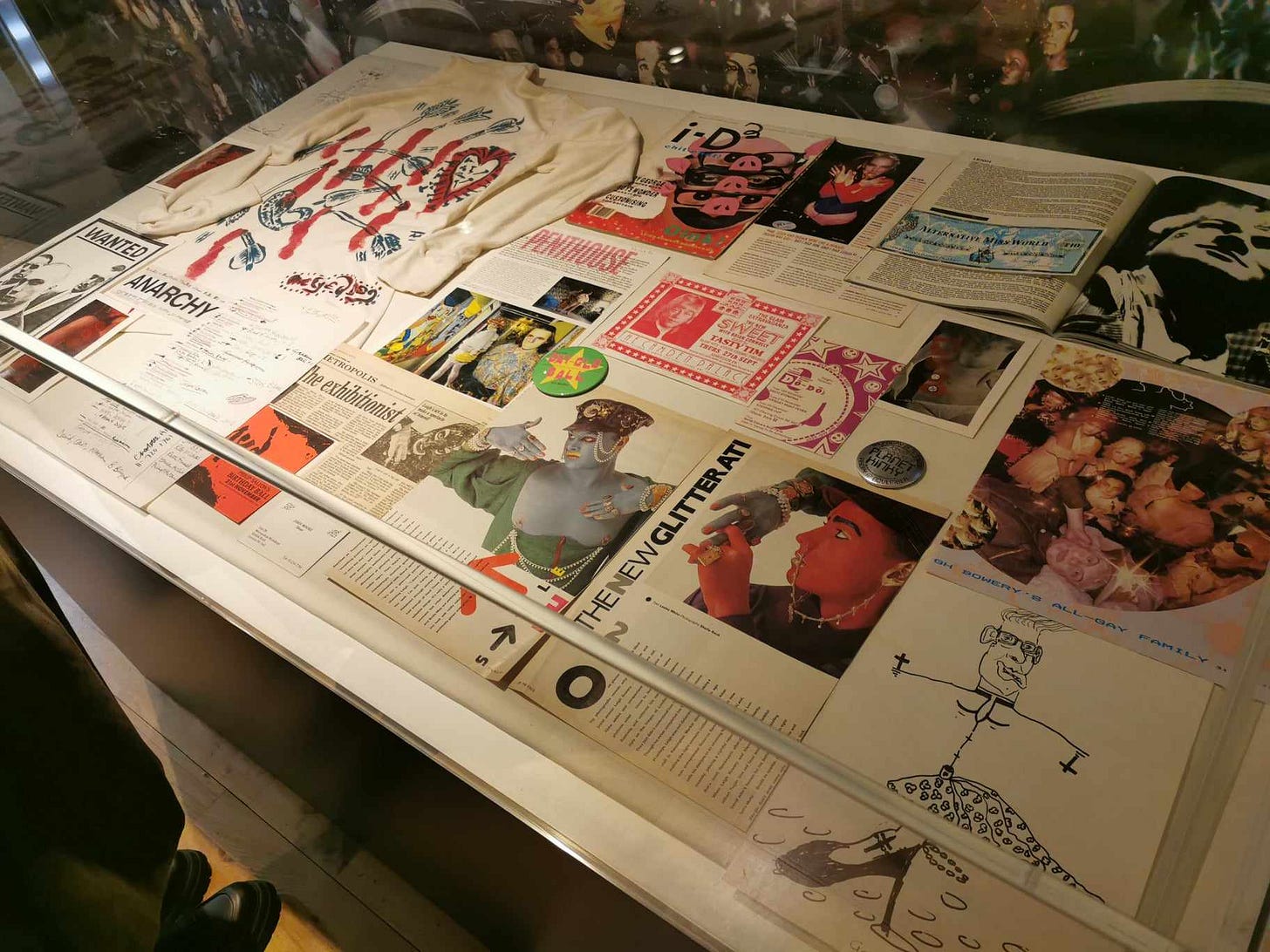

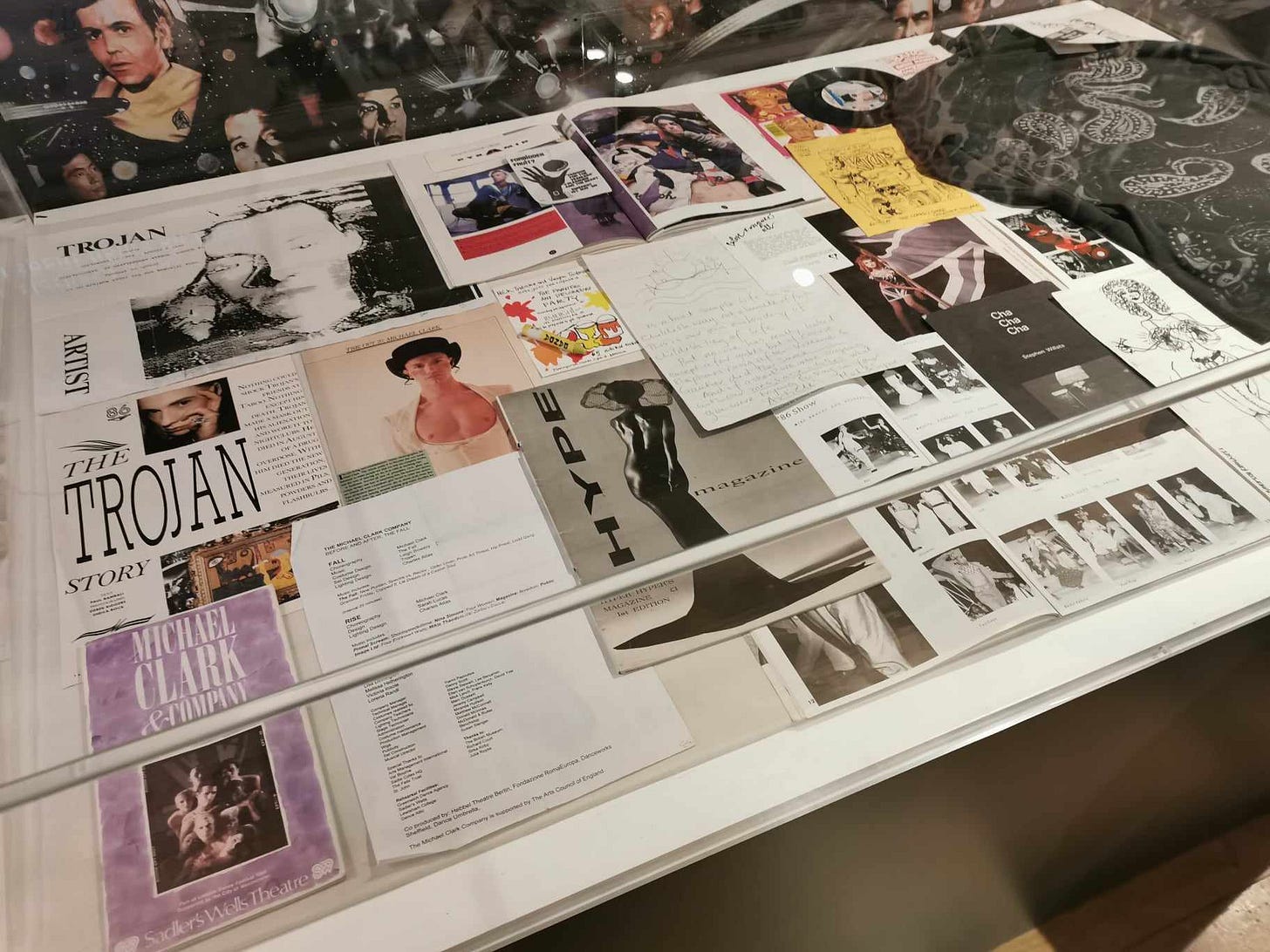

The exhibition is well researched in terms of unpacking the nuances of small designers criss-crossing between partnerships and retail outlets in the early 80s, when little more than basic financial survival to support one’s commitment to the scene could be eeked out. Thankfully, the exhibition text displays didn’t have any of the lazy broad-brush references to the new romantic scene being a microcosm of Thatcher’s entrepreneurialism.

The main stalling point for me was how it had all been put together to run as a kind of time-line of Leigh Bowery’s life. There is the January 1985 moment when he starts his club Taboo at Maximus, and in many ways this can be thought of a pivot of the decade. From that point onwards there was a full-on dash for eccentricity and competitive wackiness. Yes, you can argue that elements of the original new romantic scene were a precursor to this, but the exhibition gives the impression of a more hegemonic random inanity through the first half of the decade.

My own experience of this time, and I confess I was not informed or old enough to grasp the full-on new romantic craziness, was of a more blended scene that more-or-less worked together as a coherent, supportive network. So, for instance, Kensington Market had a mix of weird stalls alongside vintage, punk and neo-rockabilly (Jay Strongman’s Rock-a-Cha). Outlaws seems to exclude this body of work. We get a single exhibit of Johnsons clothing, but it is the outlier gold suit they designed as a special piece. Their previous body of work, which includes incredible collections like Jive Pilots and Voodoo, is overlooked.

The more outré clothing is pushed forward, and there is a total lack of subcultural grounding. It is odd and feels like they think that subcultural clothing of the early 80s is some how less worthy or perhaps ‘mainstream’. This was not the case. Dressing subculturally meant taking a risk and doing the hard work to find clothing and put a look together. You had a sense of style, but it was still an outsider position. It feels like, for the Outlaws, style is a dirty word. Bowery’s costumes, and the designers from the various art schools he worked alongside, have more of a lineage to surrealism, and one can think of Salvador Dali’s grand entrance at the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London where he sourced a diving suit. It was decorated with plasticine hands, a jewelled dagger, and topped with a radiator cap. Further accessorising included two Irish Wolfhounds who managed to get their leads entwined around his legs at the moment of restrictive chaos. Dali had to be inserted and screwed into the costume, and the maker of the suit (diving specialist Siebe & Gorman) assumed he was actually undertaking a deep-sea dive – on asking him to what depth he intended to venture he replied “to the depths of the subconscious”.

The exhibition has some clever touches such as reimagining Kensington Market with the cheek-by-jowl booths, and also a reconstruction of the frontage of the important shop Browns. This shows how the clothing moved into an exclusive buffer zone between street and mainstream as the new romantic generation (or the ones who were wealthy) settled into easy purchases of expensive, stylish clothing. Amidst the more wacky stuff that often looks like a precursor to the era of cosplay and cartoon living, there’s a few designers that I really like… with a special mention to Christopher Nemeth and his reused postal sack jackets.

The final part of the journey shows how mid to late 80s popstars took up the wacky end of these designs. There’s ABC in their cartoon-ish ‘Zillionaire’ stage, Mark Moore as he injected a glam-disco sensibility into his proto-house tracks that upstaged the Top Ten, and lesser known artists like the ex-positive punks who went on to form Boys Wonder. The mannequins attempt little precisions, like squaring off Ben’s eyebrows and rebuilding Martin Fry’s sumptuous blond wedge/fringe. This matches some of the mannequins from the start of the exhibition who stare of grimly, frozen in time… people such as Scarlett Cannon and her geometric bleached flat-top.

I bought the book but haven’t looked at it yet as it’s a Christmas present. I also did a trawl of a few other bookshops. The art bookshop near Tate Modern always throws up a surprise. They had a cheap stack of 10 Men magazines from the mid to late 00s. This was a weird encounter as I recall buying them at the time around 2005, when I was looking to rekindle my memories of 20 years earlier – the 80s. I’ve moved a few times since 2005 and the 10 Men magazines are no longer here but I recall having them and possibly binning them. The time between now and 2005 is just about the same as the time between 2005 and the 80s I was rekindling. It feels like a recursive loop, always looking back, and now looking back to a time when I was looking back. It’s interesting that Bernhard Willhelm features on the cover, so perhaps the surrealist thread that Bowery picked up has a continuity?

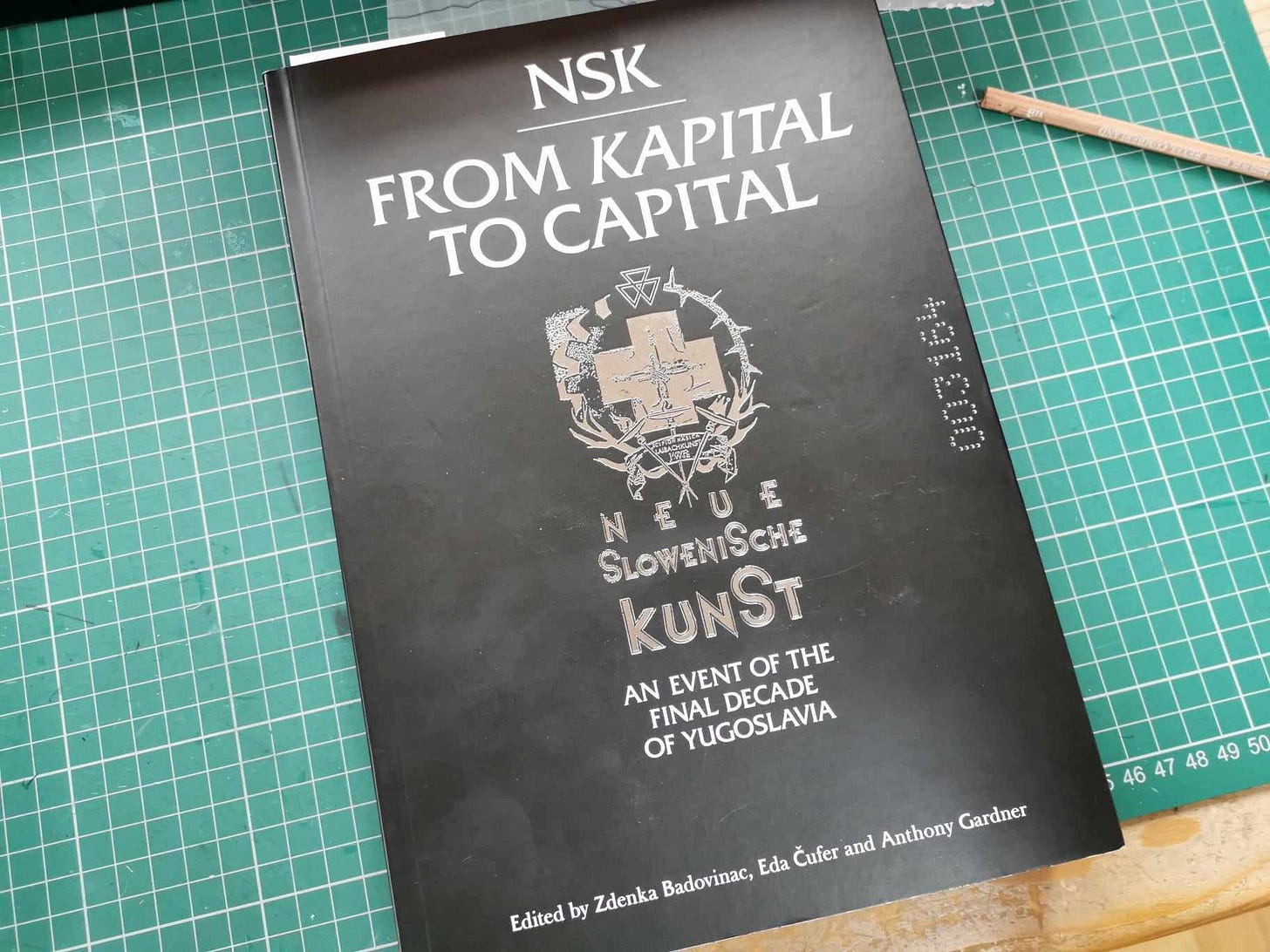

I called by Judd Street Books and was pleasantly surprised to see the expensive NSK/Laibach monograph cut down by 75% from it’s original £50 price. Laibach is another story… where did they fit into 80s style culture? When I saw them at the ICA around 1985 the lead singer had a pair of magnificent antler horns. Dali again.

The last leg of the journey, laden with large volumes, was taken on foot. The walk from Huntingdon station to our village which crosses various unlit commons and lanes and takes about 90 minutes. The long and lonely Cow Lane is a dogging spot I’m told, and once when doing the walk very late it was indeed in full swing as various headlights flashed me as I approached on foot. I kept my head down, thinking only of the cup of tea I’d be making myself in about 20 minutes.

Yesterday it was too early for any such activity, but still dark. There was a full moon but it was cloudy, so visibility was poor. Halfway across the common I encountered a herd of cows blocking the path. I didn’t know they were there until I was right upon them. Hegel used the analogy of all cows being black at night, in his opening gambit for his Phenomenology of Spirit whereby he rails against romanticism and the absolute. Scritti Politti’s Green Gartside liked a bit of Hegel in his pop-slop… that’s Green in my Sub>>Sumed ident pic. He will feature in a future essay. I’m not sure how Hegel would have processed Outlaws.

I’m looking forward to seeing this and the LB show opening at Tate next year. I agree though it sounds very London centric. It would be good to hear more about this era in the provinces. I love all the Dali references. And how surreal your walk home was.

Laibach were very much about being lost in time. European provincial kitsch, mixed with state approved realist art and militarism. At that time they were employed as extras in Kubricks Full Metal Jacket, but as they shaved their heads and wore Yugoslav military garb it wasn't much of a stretch for them to be it.